For six years, the only luxuries Bopha Sayavong dreamed of were peace, quiet, food, and shelter.

It wasn’t until she landed in Little Rock, Arkansas, as a refugee from communist Cambodia on Oct. 31, 1981, that she began to imagine the luxuries freedom would bring.

Even after arriving in the U.S., though, life was not easy.

“We just build it up from there, little by little, to figure it out,” Sayavong, now 59, told The Daily Signal in a phone interview from Marion, Illinois.

Anything would beat the four years from 1975 to 1979 she spent as a teenager in work camps created by the oppressive communist regime known as the Khmer Rouge.

Cambodia fell to communism in April 1975 when an attempted coup by the right-leaning military failed to push King Norodom Sihanouk out of power. Sihanouk then joined forces with the Communist Party.

After a five-year civil war beginning in 1970, the Khmer Rouge had seized enough land to end the conflict. However, the communists didn’t restore power to Sihanouk, but to the ruthless leader Pol Pot, who historians hold responsible for the deaths of 2 million Cambodians.

Once the communists seized Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh, they told all residents to evacuate to the provinces for three days.

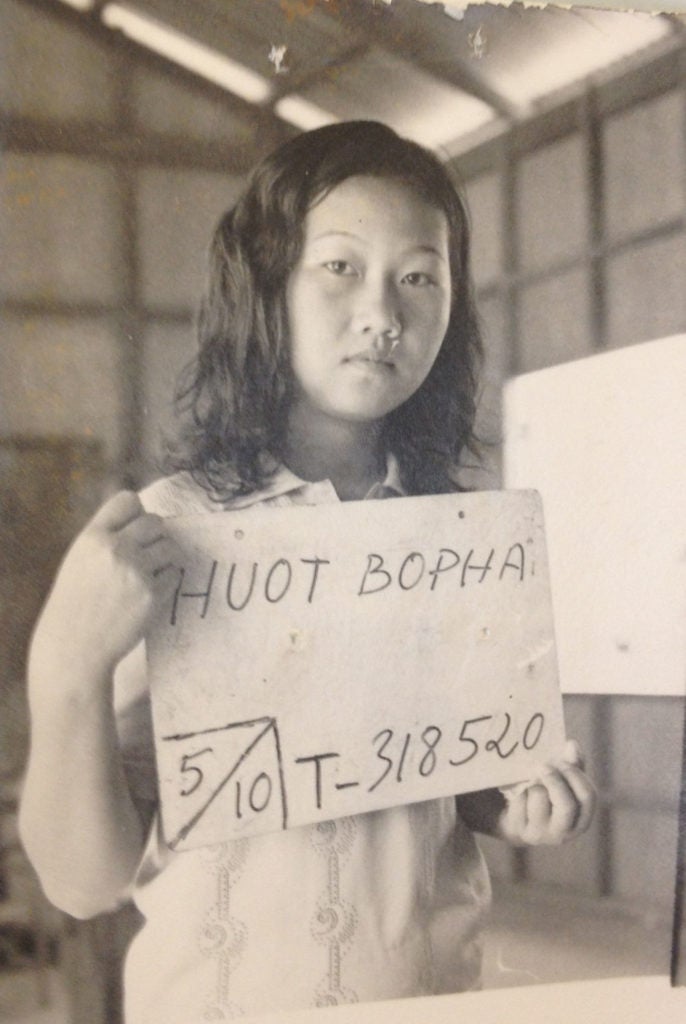

Sayavong, whose name then was Bopha Huot, was 13. Her father was a small business owner who, while in the Cambodian army, had helped Americans training during the Vietnam War. Her family was considered to be in the lower ranks of the upper class.

“The evacuation was supposed to be three days, leave your home and return back in three days, but actually it … was a false statement. It was a lie by the communist regime just to take people out of their homes,” Sayavong said.

During the four years of the Khmer Rouge’s reign, the government owned all resources; currency did not exist.

Sayavong said she was separated from her family during the evacuation as all Cambodians were divided by age, sex, and marital status. It was four years before she was reunited with her family.

“Their model is that everybody is equal, nobody is richer, nobody is poor,” Sayavong said of socialists and communists. “Sounds great, isn’t it? But that’s not true because the government owns everything. So guess who is the richest one? The government.”

She added:

People that refer to themselves as the millennial [generation], they have no clue what socialism is. I lived in both socialism and communism, and then I lived in the world of the U.S. One thing I can tell you is there is no place like the U.S. …

People think [socialism] is so wonderful, it’s so fantastic, but that’s not true. It’s just like a painting: It looks fantastic, but when you live in it, then you know it.

What about young Americans’ attraction to socialism?

“It brings me pain to even think that our children go that far,” she said. “I do believe in equality. I want … no rich, no poor, all even. But as a human being, think about it: If the government tells you what to do, how to eat, how to breathe, how could that be equal? They are above you.”

Nearly 2 million Cambodians died between 1975 and 1979 as a result of the promised equality under Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge regime.

Life under the communists was oppressive, and there was no such thing as a “full” stomach in the work camps, Sayavong said:

In the very beginning, they gave you a reasonable amount of portions, but [it] is never a generous amount and it’s never what you want to eat. Whatever they provide, that’s what you eat.

Let’s just say today you’re going to have vegetables and rice; that’s what you have, vegetables and rice. And tomorrow, maybe you have a meat. But as the times goes by, as it’s progressed, like in the second year or so, you lose even more [food]. The third year you get even less. You get to the point where you have one tablespoon of rice a day. It’s not one serving, it’s [for] a day. They don’t even have enough salt.

We … were so hungry, we eat grass and wild vegetables, and I don’t mean the grass that a cow eats. I mean any wild vegetation. We’d just taste it to see if it can be eaten, [then] we eat it. But our stomach is not made to digest those kind of plants. We don’t have two or three layers like the cows. So most people have disease, and the water is not treated [but] dirty.

Her malnutrition was so bad, Sayavong said, that she couldn’t see at night from a lack of proper vitamins and minerals to support night vision.

There was no clock in her work camp; workers would start when the sun came up and stop when it went down. She said she worked every day in the fields to stay alive.

“You wake up in the morning, you go to work … ,” she said. “When you cannot work, they will decide to eliminate you because you are a waste of their food and supply.”

She added:

They want everybody equal. So they have you work the field, building [a] village, growing rice, and farming because in order, in their stupidity, in order for you to be equals you have to start somewhere equal. …

So they have everybody start at the same thing. They abandon the manufacturer, they abandon cattle ranges and all those stuff, they start everybody on the same level. Except themselves. Everybody else, except themselves. They don’t work, they manage you.

“You know, I prayed every night, silly as that sounds,” Sayavong recalled. “I didn’t know what God I’m praying to at the time. I was hoping my … breath would never come the next morning, because it’s just unbearable. And each day I say, ‘God, please, just take me, I’m ready.’ … This is not it. I kept waking up. Never die.”

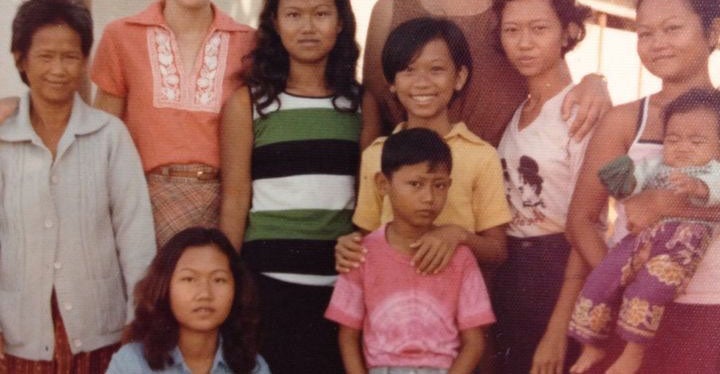

With the fall of the Khmer Rouge and end of its work camps, Sayavong said, she wandered through the jungle and found her mother, brother, and sister. Her father had died in a work camp.

In the jungle, her sister had discovered a poncho-covered boy hiding from the rain. It turned out to be Tom, a family friend before the communists had taken over and segregated everyone.

Tom was 10 when his family died in the work camps, Sayavong said.

Her family adopted him.

To survive, Sayavong said, she spent the next year smuggling food on the border with Thailand. One day, a group of Americans with a “little red cross on their arm” came to the rescue, she recalled.

The American Red Cross set up refugee camps in Thailand for Cambodian citizens fleeing their country. After two years in a refugee camp in Khao-I-Dang, Sayavong’s family was transferred to a camp in the Philippines where they eventually found a friend who was a U.S. citizen and would sponsor them.

Finally, it seemed as if there would be some security. Sayavong went through an immigration process that took her and her family to Little Rock, Arkansas.

With the assistance of a local church, she learned to speak English, got a job in a factory that paid $3.25 an hour, and earned her GED certificate.

Today, Sayavong works as a pharmacist in southern Illinois.

She has been married since 1984 to Patrick Sayavong, a refugee from Laos whom she met in Arkansas at a Baptist church. They have two daughters—Sarah, 30, and Nicole, 22.

“There’s some heartache, and there’s some misstep, and that’s just part of life,” Sayavong said. “There are things we’ve done right, and there are things we’ve done wrong. You just tweak it as you go each year, each time, and look at where we are right now.”

Editor’s note: Bopha Sayavong is a longtime friend of the parents of the reporter, who has known her since age 9.