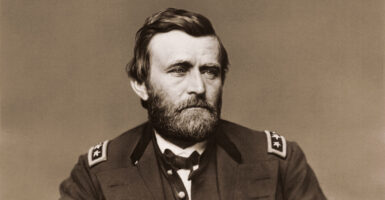

Our 18th president, Ulysses S. Grant, often is described as three things: a “butcher” general who mindlessly sent his soldiers into battle; an ineffective political leader who allowed corruption to fester in the highest levels of government; and an irresponsible human being who reveled in his drinking habits.

Although there is some truth in these stereotypes, Grant should be understood as a significant figure in American history, whose reputation was sullied after his presidency by ex-Confederates promoting the “Lost Cause of the Confederacy” through books, newspaper articles, and speeches.

This negative view of Grant subsequently became the mainstream and continues to be so to this day.

Recently, historians have begun to reevaluate their perspective on Grant, praising his work as a Civil War general and, later, as the nation’s chief executive. In 2017, biographer Ron Chernow published a critically acclaimed biography of Grant that led to a miniseries on the History Channel.

Especially in today’s charged political climate, this revitalization of Grant’s legacy is welcome news because history should properly recognize his efforts in helping America live up to her founding ideals.

Born in Point Pleasant, Ohio, in 1822, Grant graduated from West Point and served in the Mexican-American War, where he earned accolades for his service. After the war, he married into a slaveholding family, but the use of slaves on his father-in-law’s farm “was a source of irritation and shame to Grant.”

Even though he did briefly own one slave, Grant simply freed him before the start of the Civil War.

When the war began in 1861, Grant volunteered for the Union Army and quickly rose through the ranks, eventually becoming President Abraham Lincoln’s most trusted general.

Where other Union generals were indecisive, Grant spared no effort in fighting the rebels. He effectively split the Confederacy into two when he won the Siege of Vicksburg in 1863, and accepted Gen. Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox in 1865.

By the end of the war, his initial ambivalence to slavery turned into an abiding conviction that the institution was morally unjustifiable—a conviction that would drive his support in the White House for the rights of newly freedmen.

Elected president in 1868, Grant knew that a great task was before him. Slavery had been abolished, but racism remained. Even many Northern whites who supported emancipation rejected racial equality.

The challenge was daunting, but the new president committed himself to ensuring that the Union’s achievements during the Civil War would be preserved.

In his first inaugural address, Grant pushed for ratification of the 15th Amendment, which gave former slaves the right to vote, and it was adopted in 1870.

The recently formed Ku Klux Klan was determined to terrorize black Americans and prohibit them from voting, but Grant signed legislation that same year creating the Department of Justice we know today. Its immediate objective was to safeguard black voting rights against the KKK.

Grant also signed other legislation that enforced the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. The Enforcement Acts of 1870 and 1871 tackled Southern attempts to roll back Reconstruction. The acts authorized federal judges and U.S. marshals to oversee local polling places and enabled the president to crack down on those who sought to deny equal protection under the law.

A few years later came the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which banned racial discrimination in public places.

Ultimately, these laws would be rendered toothless as a result of Supreme Court decisions and the end of Reconstruction in 1877. But the boldness of Grant’s moves in continuing the legacy of Lincoln cannot be denied, and should not be overlooked.

The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education put it this way: “Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, but it was Grant who actually freed the slaves.”

After Grant’s death in 1885, the famed ex-slave orator Frederick Douglass said: “to him, more than to any other man, the Negro owes his enfranchisement.”

There are of course critics who write off Grant because of his personal and political shortcomings. He was an alcoholic who periodically went on drinking binges, but he restrained himself enough to become a successful war general and be elected president twice.

Popular culture considers him to be a “drunken butcher” who allowed many of his soldiers to die needlessly, but this epithet ignores the larger success of Grant’s military campaigns.

As for his time in the White House, the Grant administration did suffer from corruption and scandals committed by his close associates. But the American people never questioned the honesty of Grant, who himself was not implicated in any crime.

Grant was truly a consequential president whom Americans today should know more about. Despite his flaws, we should consider and appreciate Grant’s efforts to help America make some significant strides toward realizing the promises of the Declaration of Independence.

We have come a long way in rectifying our country’s original sins of racism and slavery, and to a great extent, that effort began with Grant.

As we grapple with our history today, it is time to fully recognize Grant’s achievements and elevate him in our national consciousness.