Among several disturbing elements of Christina Cross’ New York Times op-ed “The Myth of the Two-Parent Home” is the author’s seeming belief that unless growing up with married parents has the same effect on black children as on white youngsters, it is not worthy of endorsement.

Otherwise, asserts the Harvard postdoctoral fellow, “blindly promoting the merits of marriage and the two-parent family is not the answer.”

Her purpose appears to be to show how black families do in comparison to white families, as opposed to what the absolute impact of strengthened family structure would be on black children. Take this excerpt:

Although in general, youths raised in two-parent families are less likely to live in poverty, black youths raised by both biological parents are still three times more likely to live in poverty than are their white peers. Additionally, black two-parent families have half the wealth of white two-parent families. So, many of the expected economic benefits of marriage and the two-parent family are not equally available to black children.

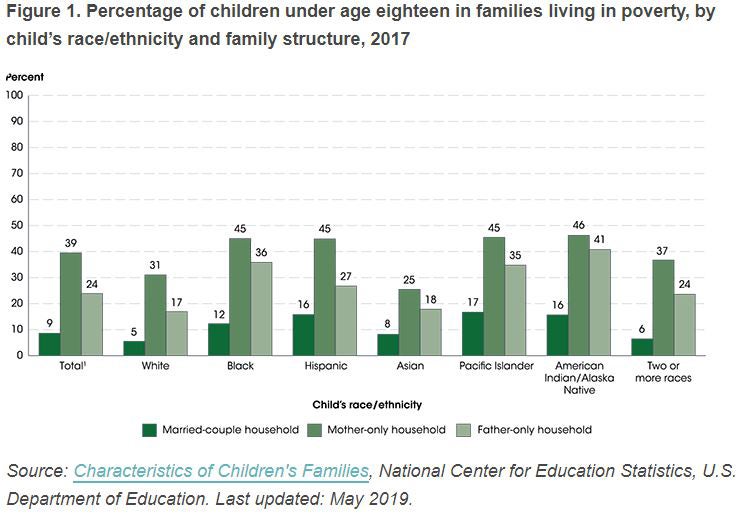

Yet the research Cross herself cites from the National Center for Education Statistics tells a far more hopeful story about the impact of family structure. Consider what we see in figure 1:

In 2017, only 5% of white children under 18 residing with their married parents lived in poverty, versus 12% of black children living with their married parents. That’s a relative multiplier of 2.4, not the exaggerated “three times” that Cross estimates with her obsession with black-white comparisons.

But far more importantly, we see that the proportion of black children under 18 living in poverty decreases from 45% for mother-only households and 36% for father-only households to just 12% for married-couple households.

That’s a huge difference and an enormous improvement that seems not to interest Cross.

To repeat: Being raised in a married-couple household led the poverty rate for black children to go down 73% compared to mother-only households and 67% compared to father-only households.

And as evidence of the power of family structure to transcend race, 31% of white children raised in mother-only households live in poverty, versus just 12% of black children living with their married parents. That is a stunning realization.

Yet Cross narrowly cites evidence that seeks to denigrate the two-parent household as a marginal thing for black children, while ignoring the data that actually cement the difference family structure plays in the lives of children of all races.

Another strange statistical technique practiced by Cross is lamenting the fact that black Americans have disproportionately high levels of family instability while not disclosing figures that would illuminate the extent of the issue.

I would urge that it is better to share the raw data, so that people can assess the actual numerical explosion in non-marital birth rates among blacks and then reasonably conclude for themselves whether these statistics do actually matter.

Take this excerpt:

America has a long and troubled history of viewing racial inequality primarily through the lens of family structure. Recall the publication of the controversial Moynihan Report in 1965, in which government officials pointed to higher rates of “female-headed households” and “out-of-wedlock births” among black Americans as key drivers of the disadvantages they face.

When Daniel Patrick Moynihan produced “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action,” he was drawing attention to what he saw as a crisis in a segment of the black community that was mired in poverty. According to the 1965 report, 23.6% of all black babies were born outside of marriage.

If the same attention had been paid to that glaring statistic then as has been paid to structural barriers around race, steps could have been taken to arrest the continuing decline in family formation that has occurred over the last five decades, not only in the black community, but across all races.

Indeed, according to the most recent census data, in 2018, the non-marital birth rate among black women reached 69.4% and the overall non-marital rate was 39.6%.

As Moynihan himself warned again almost 30 years ago in 1991, “Illegitimacy levels that were viewed as an aberration of a particular subculture twenty-five years ago have become the norm for the entire culture.”

This raises yet another peculiar aspect of Cross’ argument. By singling out black Americans as the “group whose family structures have long been used to explain their social and economic disadvantages,” she obscures the fact that the black community isn’t the only place that’s suffering from the consequences of family breakdown.

Consider another excerpt:

Black Americans have the highest rates of single-parenthood and nonmarital births in the country, and this divergence from the two-parent family ideal is routinely implicated in the lower levels of educational attainment and higher rates of poverty and unemployment within the black community.

Family breakdown is unarguably bad for black children. But what is happening with other Americans?

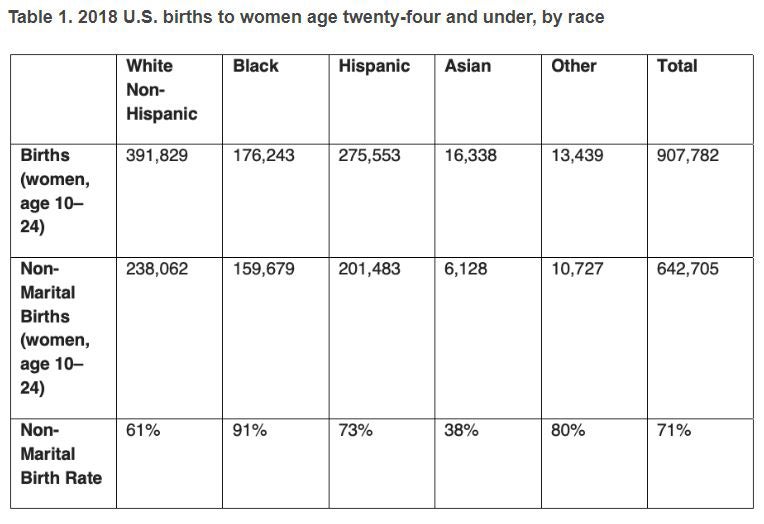

Again using birth data for 2018, Table 1 shows the non-marital birth information for women age 24 and under.

Yes, it’s staggering that 91% of the babies born to black women under age 25 were outside of marriage. But what of the 61% of babies born outside of marriage to white women age 24 and under? Their more than 238,000 children dwarf the numbers in other racial categories.

According to Child Trends, the percent of births occurring to unmarried women has grown most rapidly among white women. And there is increasing evidence that opioid deaths and other issues facing particularly white working-class men are linked to a breakdown in family stability.

Perhaps if there wasn’t such a narrative insisting that the breakdown of the family is a “black problem,” more agreement might be reached around the idea that the decline in family structure is an existential challenge facing communities of all backgrounds and one that all should tackle together.

Ultimately, Cross makes her argument clear:

[W]hat deserves policy attention is not black families’ deviation from the two-parent family model but rather structural barriers such as housing segregation and employment discrimination that produce and maintain racialized inequalities in family life.

Does it have to be one or the other? Why it is so difficult to have a nuanced conversation that both structural barriers and factors like family structure matter to determining child outcomes?

Most importantly, what do we teach the next generation about their ability to develop the personal agency to overcome those barriers? If you are 12 years old, do you have the power to solve housing segregation?

Perhaps the next generation of students should learn that a staggering 97% of millennials who obtained at least a high school degree, worked full-time, and married before having children are not poor.

Rather than pummel young people over barriers for which they have no control, maybe it would be good to share the power over decisions that they do have to determine their own destiny.

In his powerful Washington Post essay “Don’t deny the link between poverty and single parenthood,” Robert Samuelson says, “If, magically, a third of America’s poor escaped poverty, the change would (justifiably) be hailed as a triumph of social policy.”

Similarly, in her New York Times op-ed, Cross’ own analysis suggests that, while strengthening family structure is no silver bullet, there is much to be hopeful for if family structure among blacks and kids of all races were more stable.

That is not a myth.

Originally published by the Fordham Institute.