Before hitting the road for their summer vacations, the justices of the Supreme Court announced last week that they would hear a major school choice case in the next term.

If the court rules in favor of the families that brought this case, it could pave the way for educational freedom and opportunity for millions of children across the country.

The case, Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, deals with Montana’s tax credit of up to $150 per year for donations taxpayers make to a scholarship-granting organization.

The scholarship-granting organization then provides scholarships to income-eligible children to attend a private school of their choice.

Recipients may use the funds at qualified schools, which initially included religiously affiliated private schools. Then the Montana Department of Revenue enacted a rule excluding religious schools, citing the state constitution’s “no aid” provision (known as a Blaine Amendment) that prohibits public money from going to churches.

Families with children at religious schools challenged that rule, arguing that it violates their federal constitutional right to free exercise of religion.

Religiously affiliated schools make up 69% of private schools in Montana. If this rule were to be allowed to stand, it would shut out a large percentage of schools from the scholarship program, limiting the options of families that relied on this assistance to send their children to the school of their choice.

The good news is that the Supreme Court set the stage for the Espinoza case with its 2017 ruling in Trinity Lutheran Church v. Comer.

In that decision, the high court held that the state of Missouri violated the First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause when it barred a church-run day care center from receiving a grant to resurface its playground.

The state of Missouri argued that it was trying to avoid running afoul of the Establishment Clause, which prohibits states from recognizing an official state church. In doing so, Missouri trampled on Trinity Lutheran’s free exercise rights.

To be sure, there is some “play in the joints” between what the Establishment and Free Exercise clauses require of states.

Writing for the majority, Chief Justice John Roberts explained that by singling out the day care center for disfavored treatment and “denying a qualified religious entity a public benefit because of its religious character,” Missouri went “too far.”

Roberts wrote in a footnote that the decision was limited to “express discrimination based on religious identity with respect to playground resurfacing” and stressed that the decision “do[es] not address religious uses of funding or other forms of discrimination.”

Justice Neil Gorsuch disagreed that the ruling was limited.

In a concurring opinion, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas, Gorsuch concluded that the “general principles” of this decision “do not permit discrimination against religious exercise—whether on the playground or anywhere else.”

Shortly after issuing this decision, the justices instructed courts in Colorado and New Mexico to square their rulings in cases dealing with a school voucher program and a textbook-lending program with the Trinity Lutheran decision.

Thus, the scope of the Trinity Lutheran ruling remains unclear, and now the high court has the opportunity in the Espinoza case to make clear that states may not require religious organizations to check their beliefs at the door before entering the secular world.

If allowing a church-run day care center to compete for state grant money does not violate the Establishment Clause, then surely there aren’t Establishment Clause concerns raised by allowing families to use scholarship money at religious schools, for which donors receive a modest tax credit.

Indeed, in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002), the court noted the “consistent distinction” it has drawn between “government programs that provide aid directly to religious schools … and programs of true private choice, in which government aid reaches religious schools only as a result of the genuine and independent choices of private individuals.”

On several occasions, the high court has rejected Establishment Clause challenges to “neutral government programs that provide aid directly to a broad class of individuals, who, in turn, direct the aid to religious schools … of their own choosing.”

The state’s Blaine Amendment also should not provide cover for preventing families from choosing to use these scholarship funds at religious schools.

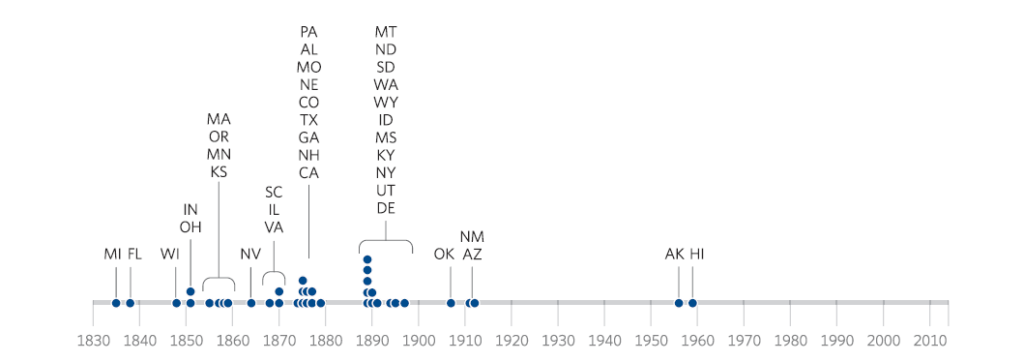

Source: Lindsey Burke and Jarrett Stepman, Journal of School Choice, Blaine Amendment adoption

More than three dozen states have Blaine Amendments, named for Sen. James G. Blaine, R-Maine, who in the late 1800s pushed for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution prohibiting aid to “sectarian” schools.

As Thomas explained in the 2000 decision Mitchell v. Helms, “Consideration of the amendment arose at a time of pervasive hostility to the Catholic Church and to Catholics in general, and it was an open secret that sectarian was code for Catholic.”

Although Blaine failed in his bid to amend the Constitution, many states—some on condition of statehood—adopted their own Blaine Amendments.

Today, these ignoble 19th-century amendments often thwart modern-day school choice efforts as more and more states move toward systems that enable families to direct their child’s education funding to education options that work for them.

With any luck, the court will use the Espinoza case to heed Thomas’ advice that “this doctrine, born of bigotry, should be buried” and pave the way for school choice across the country.

The justices will hear oral argument in the Espinoza case during their next term, starting in October, and release a decision by the end of June 2020.