Despite a solid year for investment returns, the unfunded liabilities of state and local government pension plans increased by $433 billion, the most recent estimate from the American Legislative Exchange Council shows.

According to ALEC’s report—which uses more appropriate assumptions on investment returns than the plans use themselves—state and local governments’ unfunded liabilities now exceed $6 trillion.

That’s a whopping $18,676 for every man, woman, and child, or nearly $50,000 for every household in America.

This is bad news for taxpayers in states and localities where government workers have been promised far more in pension benefits than politicians set aside to pay them. That’s because most states have strong protections for promised pension benefits, meaning there is little prospect of reducing a pension benefit or asking employees to contribute more to it.

Contractual or constitutional obligations for government pensions could mean that paying the pensions of retired government employees may take precedent over paychecks for current employees.

Moreover, some state constitutions prevent any changes to government employees’ pension benefits. That means current government employees can’t ever be required to contribute more to their pension plan than they did on the first day they were hired. And, actually, not a single term of their initially promised pension benefits ever may be altered.

Just imagine how detrimental it would be to private employers if they never were allowed to alter the benefits they initially offered their employees.

With an average funding ratio of only 33.7 percent across state and local pensions and every single state at risk of defaulting on pension obligations (as measured by Pension Protection Act standards, assuming a risk-free rate of return), taxpayers across all states face significant tax increases to pay for their governments’ unfunded pension promises.

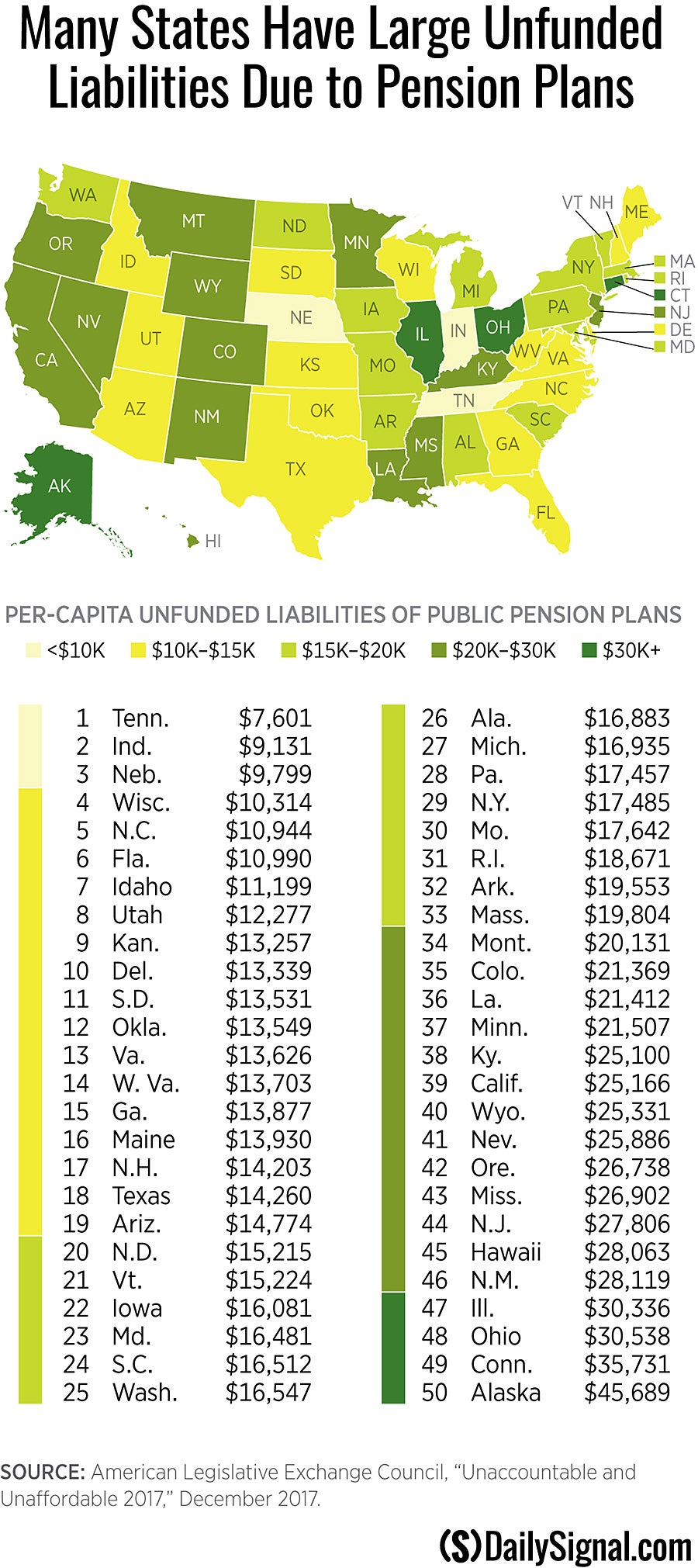

Taxpayers in certain states are looking at greater risks and liabilities than others, however.

Taxpayers in Tennessee, Indiana, Nebraska, Wisconsin, and North Carolina, for example, must deal with the lowest unfunded liabilities per person, ranging from about $7,600 to $10,900.

Taxpayers in Alaska, Connecticut, Ohio, Illinois, and New Mexico, on the other hand, face the highest unfunded pension liabilities, ranging from about $28,100 to $45,700 per person.

Overall, the American Legislative Exchange Council estimates that pension plans have only about a third of the funds on hand—33.7 percent—that they need to pay promised benefits. Some states have significantly lower funding levels, which means they are at risk of running out of funds in the near future.

Once a state or local pension plan runs out of money, taxpayers have to fund the pension benefits of retirees as well as the contributions of current employees.

Connecticut, Kentucky, and Illinois have the lowest funding ratios, at 20 percent, 21 percent, and 23 percent respectively.

Already, Illinois spends as much on pensions as it does on welfare and public protection (that is, police and firefighters) combined, and nearly half of its education appropriations go toward teacher pensions. If the state’s pension plans reach insolvency, pensions could become its single biggest cost.

Some states have taken measures to improve the outlook for their pension plans, such as shifting new employees to defined contribution retirement plans, limiting future pension benefits, reducing unrealistic interest rate assumptions, and actually making the annually required pension contributions. But the rising tab for unfunded state and local pension liabilities shows most states have failed to address massive shortfalls.

One motivation for states not to address their pension shortfalls is the hope or expectation of a bailout by federal taxpayers. This would force taxpayers in more fiscally responsible states to pay for the financial recklessness of more spendthrift states.

Lawmakers in Washington need to send a strong signal to states that a federal pension bailout is not an option.

Rep. Brian Babin, R-Texas, has introduced a bill that would do just that. His legislation, called the State and Local Pensions Accountability and Security Act, would prohibit the U.S. Treasury and the Federal Reserve from providing any form of bailout or financial assistance to a state or local pension plan.

Unless state and local lawmakers know that a federal bailout is not an option, as Babin’s bill proposes, they will have little incentive to enact much-needed pension reforms now.