Colin Kaepernick meant to do no such thing, to be sure, but by benching himself during the national anthem because America “oppresses black people,” and then wearing a shirt celebrating actual totalitarianism and racism in Cuba, he has provided us with textbook compare and contrast case studies.

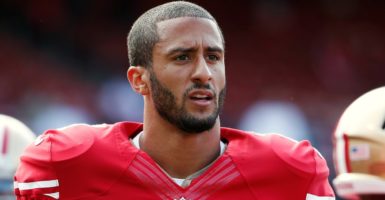

To be clear, to appreciate this silver lining is not to condone his actions. The erstwhile starting quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers doubtless has a constitutional right to express his opinion, even when it’s wrong. But his actions unleashed a firestorm of criticism.

When he sat during “The Star-Spangled Banner” before a game last Thursday because “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color,” Kaepernick insulted many people, and not just those who have lost limbs or family members in defense of the country.

When he showed up at the postgame press conference sporting a T-shirt with photos of Malcolm X meeting Cuban dictator Fidel Castro in the 1960s, Kaepernick also revealed either ignorance of communism and of Cuba, or a troubling ideological proclivity.

But tolerance of other views, no matter how heinous we deem them, is one of the things that should separate conservatives from liberals. The former rightly chide the latter for being at best “cupcakes” needy of “trigger warnings” and “safe spaces”—and at worst despots all too willing to unleash the language police to silence their fellow citizens.

So let’s celebrate the opening Kaepernick has given us to debate these matters openly in the marketplace of ideas. America is not without blemishes, yes, but let’s count the ironies implied in his perhaps well-meaning actions.

The constitutional protections that safeguard Kaepernick’s speech and actions are limited to a minority of the world’s 7 billion residents, and are in many ways the reserve of the 300 million of those people who happily call themselves American. There are many constitutions around the world, but many are not worth the paper upon which they’re written.

Cuba’s communist government particularly represses every freedom. Freedom House singled it out last year as the state that “has the most restrictive laws on freedom of expression and the press in the Americas.”

Havana’s tyrants even dispense with fig leaf protections they won’t respect. Their constitution bans outright the free speech that Kaepernick so enjoys unless it “conforms to the aims of a socialist society.”

As Freedom House put it, “Article 91 of the penal code prescribes lengthy prison sentences or death for those who act against ‘the independence or the territorial integrity of the state,’ and Law 88 for the Protection of Cuba’s National Independence and Economy imposes up to 20 years in prison for acts ‘aimed at subverting the internal order of the nation and destroying its political, economic, and social system.’”

The constitutional protections that safeguard Kaepernick’s speech and actions are limited to a minority of the world’s 7 billion residents, and are in many ways the reserve of the 300 million of those people who happily call themselves American.

The nation whose symbols Kaepernick refuses to honor also is institutionally constructed to deal with problems. We have seen this with the abolition of property requirements for voting, the scourge of slavery, the extension of the franchise to women, the civil rights movement, etc.

Abraham Lincoln was a believer that the Founding documents had prepared America to accomplish what he set out to do. The idea contained in the declaration that “All Men Are Created Equal” was not needed for the fight the British, for example, “but without it, we could not, I think, have secured our free government, and consequent prosperity,” he wrote at the outset of the war.

A century later, Martin Luther King made the same point in the “I Have a Dream Speech,” when he said the Founders had written a promissory note that all men—“yes, black men as well as white”—would be guaranteed their unalienable rights.

With Jim Crow, America had defaulted on this promissory note, King said. But unlike Kaepernick, King believed in the institutions: “We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. So we’ve come to cash this check.”

And what of the communist institutions and government of Cuba? That poor island’s many Afro-Cuban dissidents tell us again and again of the depredations they suffer.

Kaepernick could use his fame to try to save the life of Guillermo Fariñas, the brave Afro-Cuban dissident on death’s door after 39 days of a hunger strike he launched to protest being tortured. The winner of the 2010 Sakharov Prize, the European Union’s highest award, says he will either die or get the communist government to agree to stop using violence against dissidents.

Or Kaepernick could talk to Yris Tamara Pérez Aguilera, the president of Cuba’s Rosa Parks Civil Rights Movement. I did two years ago and she was full of contempt for the Congressional Black Caucus, which, like Kaepernick, seemingly, has a weak spot for Havana’s dictators.

“They should look closely at Cuba’s Council of State, and see how many black Cubans they find there,” she said. And of course she is right. Take a look at the current lot and you will see that the Politburo and the central committee of the party are dominated by whites in a country with a majority of color.

Indeed, Castro’s family and the communist oligarchy look like this when they’re whooping it up around the world, while the dissidents look like this after they’re attacked.

Free elections would do much to reverse this imbalance. Kaepernick could talk to Oscar Biscet, whom many say would become Cuba’s president if the Castros relented and allowed democratic elections. Alas, communist Cuba lacks the institutions and freedoms that Kaepernick has in America—institutions and freedoms that, regardless of his disrespect, still protect his actions.