A new issue governing requirements job-seekers must satisfy to work in fields ranging from interior design to cosmetology is gaining bipartisan support on Capitol Hill and at the White House.

Policymakers have turned their focus to occupational licensing, and an unlikely alliance of leaders across the political spectrum has emerged with hopes of easing state and local licensing requirements, linking Republicans and Democrats, as well as the Obama administration and Charles and David Koch.

That alliance was on full display Tuesday at a Senate Judiciary subcommittee hearing spearheaded by Sens. Mike Lee, R-Utah, and Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., which featured testimony from top Obama administration officials and center-right organizations.

“Occupational licensing has benefits and costs,” Dr. Jason Furman, chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, said at the hearing. “Licensing is usually justified on the grounds that it improves quality and protects safety.”

Few disagree that those working in professions dealing with the public’s health, safety, and welfare—doctors, pilots, lawyers—should be required to obtain a license. However, over the last 50 years, occupational licensing has grown substantially.

“While these regulatory regimes in many cases serve to ensure the health and safety of consumers, in a growing number of cases, they have been expanded beyond that purpose in ways that harm competition,” Lee said during the hearing. “This happens when the regulations, instead of being limited to safety concerns, protect incumbents by imposing inordinate costs on would-be market entrants, leaving consumers with higher prices, fewer choices, and less innovation.”

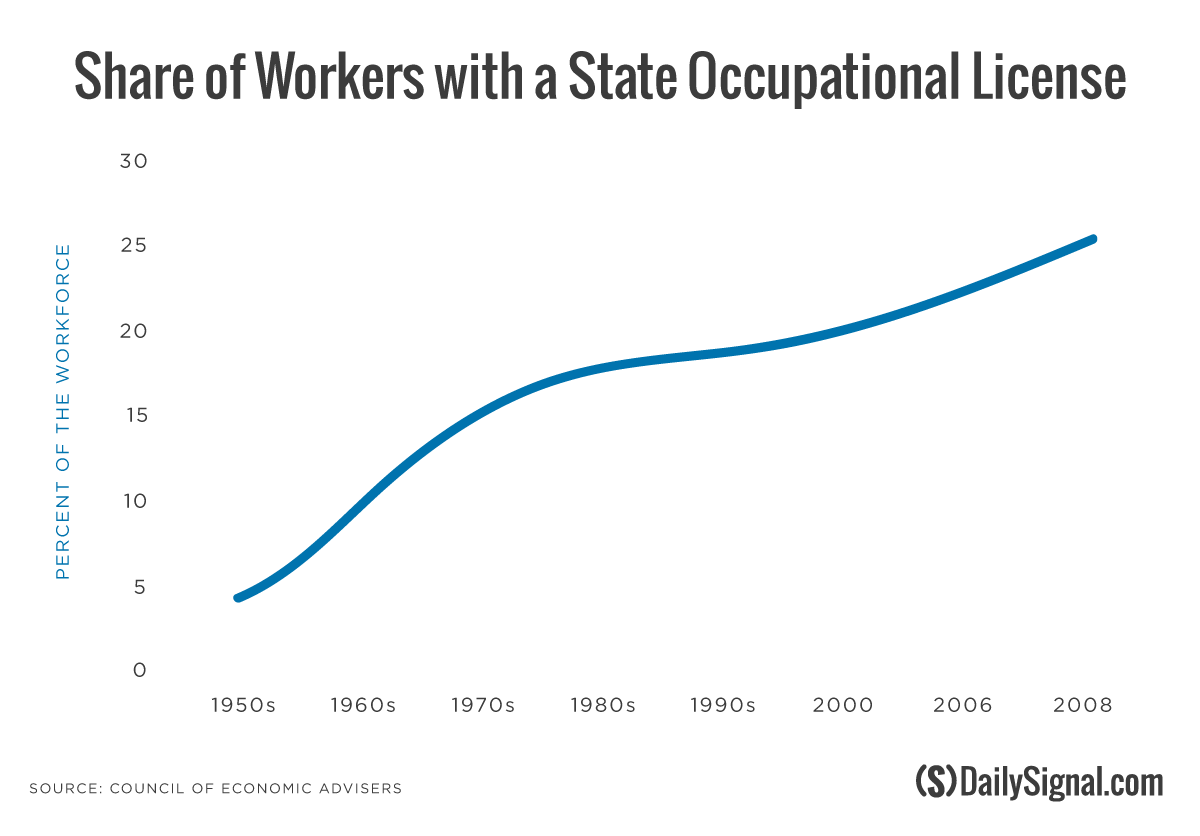

According to a study released by the White House in July, the percentage of the U.S. workforce covered by licensing laws grew from under 5 percent in the 1950s to 25 percent in 2008. According to the report, two-thirds of the change is related to an increase in the number of professions that require a license.

“The goal here is pretty obvious,” Klobuchar said at the hearing. “Licensing is important when it protects the health and welfare of consumers or the safety of professionals. We know we need that. But restrictions should not limit the opportunities of workers, of small businesses, of millennials, of spouses of armed service members—you name it.”

Occupational licensing refers to state and local rules that require a job-seeker to obtain approval from a government-sponsored board before he or she can begin working in an occupation. The Institute for Justice, which has emerged as a leader in the occupational licensing debate, describes it as “government permission to work in a particular field.”

Jobs range from makeup artists, which require licenses in 36 states, to upholsterers, which require licenses in seven states.

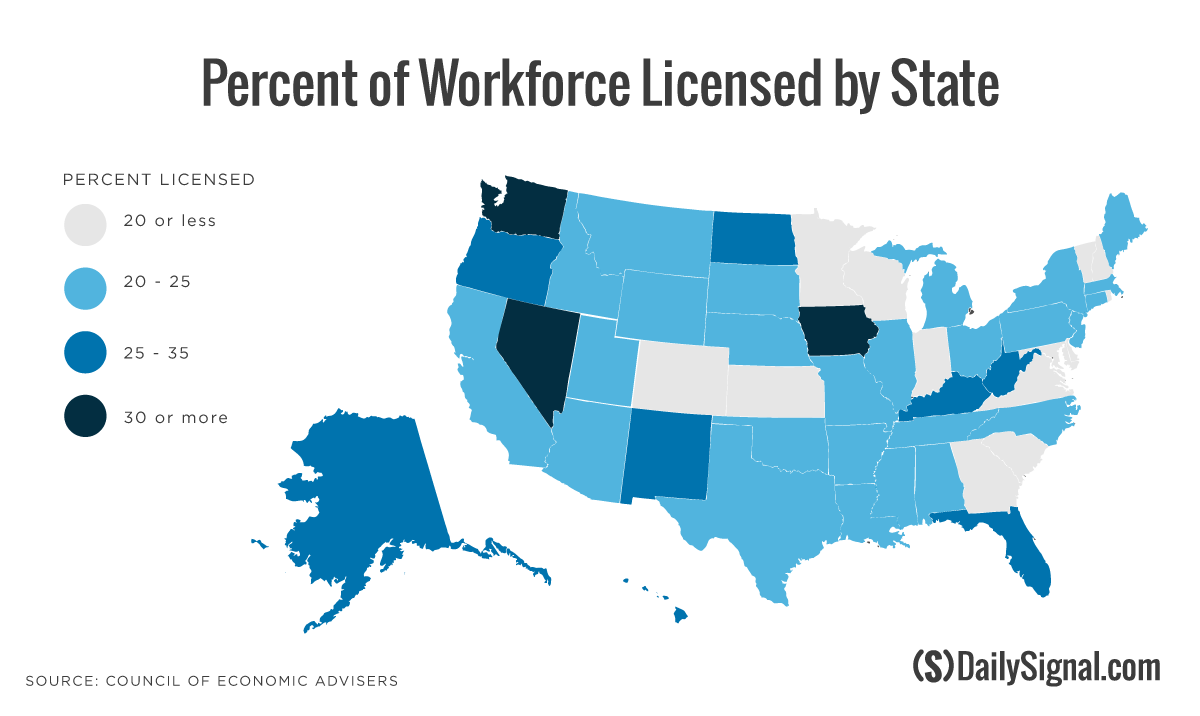

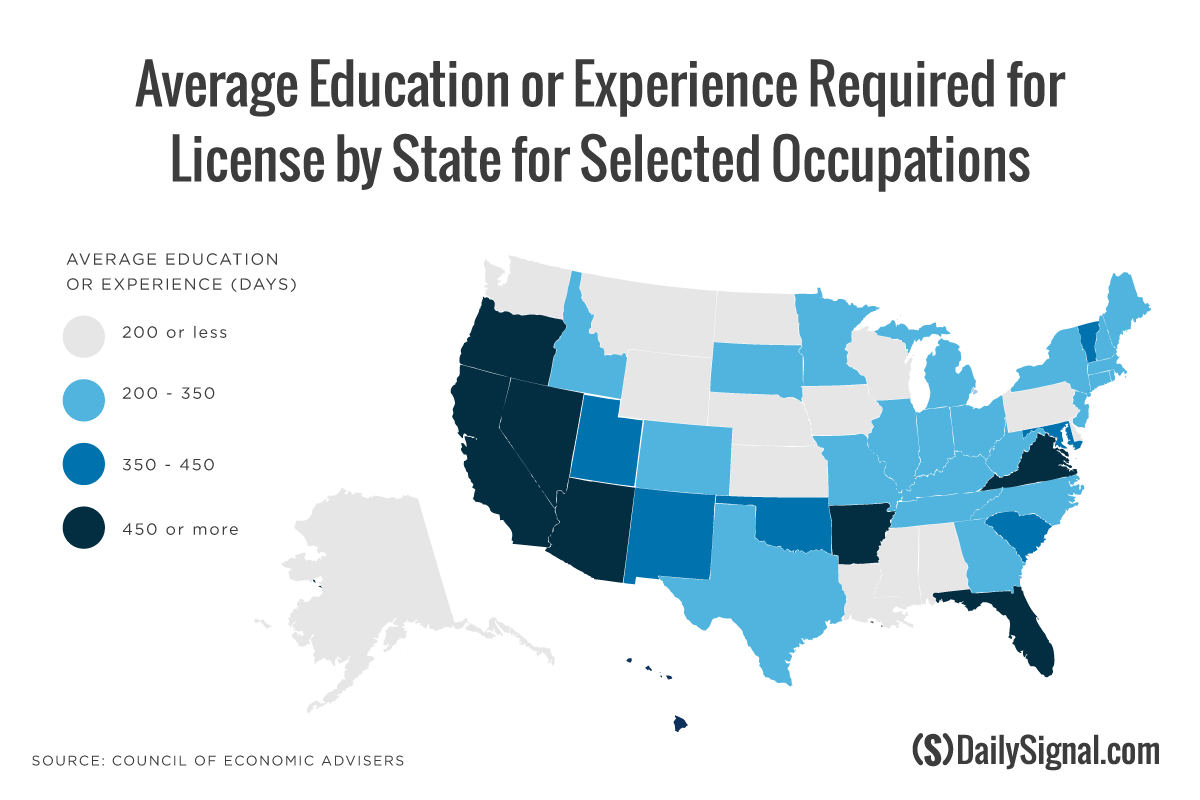

Occupational licensing requirements differ by state. In some cases, those seeking a license to work in a specific occupational must pay costly fees and complete mandated hours of required training before receiving approval from a government-sponsored board to work.

Such barriers to entry into various fields, experts warn, put onerous burdens on those trying to enter the workforce and can have negative effects on low-income job-seekers looking to break into licensed fields.

“While licensing requirements can lead to higher wages for those able to obtain a license, they can also reduce employment opportunities and depress wages for excluded workers,” Furman said. “Licensing laws also lead to higher prices for goods and services, in many cases for low-income households, which are not always justified by improved quality or public safety.”

The number of occupations requiring licenses across the 50 states range from a high of 71 in Louisiana to a low of 24 in Wyoming, according to the Institute for Justice. And for many seeking licensed jobs, it can take months or even years of education and experience to obtain a license to work.

In Nevada, for example, the education and experience requirement for an interior designer is more than 2,100 days, or six years, according to the Institute for Justice. The education and experience requirements for barbers in Nevada is 890 days, more than two years. Meanwhile, the education and experience requirement for an emergency medical technician in the state is 26 days.

Not only do experts warn that occupational licensing can put burdens on job-seekers, Klobuchar stressed that licensure can prevent job-seekers from moving across state lines, which disproportionately affects military spouses, specifically, as roughly 35 percent of military spouses work in jobs that require licenses.

When compared to civilians, the spouses of those serving in the armed services are 10 times more likely to have moved across state lines in the past year, according to the White House.

“Licensing requirements differ from state to state because interstate reciprocity is rare—these are limiting people’s ability to move. Instead, our economy, as you know, this new ‘gig economy,’ needs to accommodate flexibility,” the Minnesota senator said. “Millennials face a rapidly changing job market. Spouses of armed service members are constantly on the move.”

Beginning as early as April, the White House has engaged in discussions about the rise of occupational licensure with interested parties, most notably the network run by Charles and David Koch.

Last month, Mark Holden, general counsel for Koch Industries, and top Obama adviser Valerie Jarrett met to discuss efforts to roll back licensing requirements.

Holden didn’t appear at Lee’s hearing Tuesday but commended Lee’s and Klobuchar’s work on the issue.

“As a growing number of policymakers and Americans realize, the steady growth of occupational licensing in recent decades has created many barriers to opportunity that prevent many Americans, including the less fortunate, from finding a career or starting a small business,” Holden wrote in a letter to the senators.