In a time of anxiety over border security, the so-called fiancé visa is one avenue into the United States that has generated little attention.

But the normally low-drama visa that facilitates marriage is now under scrutiny after it became known that one of the shooters in the San Bernardino terrorist attack used the visa to enter the U.S.

The smooth path taken into this country by the now deceased female suspect in the attack, Tashfeen Malik, has pushed the Obama administration to launch a review of the program, as White House Press Secretary Josh Earnest has said the vetting process for what’s formally known as the K-1 visa is “not as strict” as the screening for refugees.

Yet according to immigration experts, people applying for the fiancé visa, which allows foreigners to enter the U.S. to marry an American citizen, go through some of the toughest screening requirements before being admitted here, experiencing a more thorough vetting than foreigners looking to visit.

“It has one of the stronger screening processes,” said Alex Nowrasteh, an immigration policy analyst at the Cato Institute, in an interview with The Daily Signal. “If there was an effort to limit or stop the program, it would be an unprecedented infringement on Americans’ ability to choose who they want to marry.”

According to Nowrasteh, obtaining a fiancé visa usually takes six to nine months.

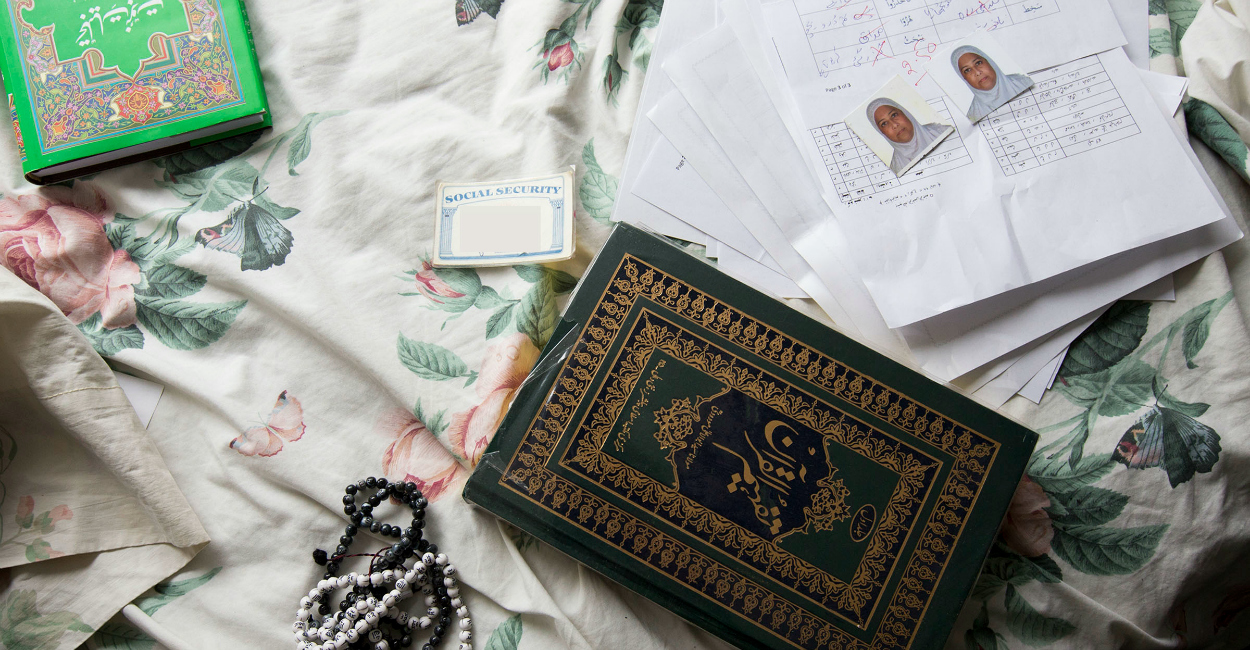

Applicants have to provide fingerprints and undergo background checks, biometric tests, and medical screenings and be interviewed by U.S. embassy staff in their country of origin.

The partner who is a U.S. citizen also has to get a criminal background check. To prove they are together and intend to marry, the couple have to have met at least once in the previous two years and show photographs or other evidence, like a wedding invitation or personal messages.

After the foreigner receives the visa, the couple must marry within 90 days. After that period, the visa expires and cannot be renewed.

Once married, the visa-holder can apply for permanent residence.

In the first nine months of this year—the most recent data available—36,627 people applied for K-1 visas, with 3,727 requests rejected.

Between 2005 and 2013, according to the Department of Homeland Security’s Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, there were 262,162 fiancé visas granted, about 29,000 per year.

Pakistan, where Malik was born, accounted for 272 K-1 visas in 2013. Saudi Arabia, where Malik later moved, accounted for 21 K-1 visas that year.

So far, Congress seems content with the program, but lawmakers plan to review it as part of a wider investigation of the various ways foreigners can enter the U.S.

The House has already passed bills limiting the Syrian refugee resettlement program and toughening the visa waiver program, which allows citizens of 38 countries to travel here without a visa.

Rep. Mark Meadows, a leader of the conservative House Freedom Caucus, told The Daily Signal that lawmakers are approaching the fiancé visa program differently from how they did the Syrian refugee issue, which was addressed quickly after the Paris terrorist attacks.

“I don’t see us addressing the fiancé visa program as much,” Meadows, R-N.C., said. “I do believe we need to take seriously this one incident and to certainly not turn a blind eye to the risks. But you are dealing with one situation where you have a U.S. citizen and the potential of making things difficult on their soon-to-be wife or husband, and the other situation [the refugee program] that is totally discretionary and that’s based on administration policy or State Department policy—one that is thrust upon us.”

According to The New York Times, Malik went through two rounds of criminal and national security checks to earn her fiancé visa and, later, a resident green card to live in the U.S.

The checks flagged no negative information, The Times reported.

Malik was granted the K-1 visa in Pakistan in July 2014 and traveled to the U.S. that month.

The AP reported that Malik married her husband, Syed Farook, an American citizen and her partner in the shooting, in August 2014, within the 90-day time limit.

Malik received a conditional green card in July 2015, according to the Times. After two years, she would have had to apply for a regular green card, proving the couple remained married.

James Comey, the FBI director, testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee on Wednesday, said, “It’s too soon to know what, if anything, might have been missed in the screening process.”

For at least one senator known to be tough on immigration, Malik’s ability to enter the country without suspicion is enough to warrant change to the fiancé visa program.

“We absolutely need to investigate and reform the fiancé visa,” Sen. Jeff Sessions, R-Ala., told The Daily Signal. “It is clearly vulnerable to infiltration and fraud and provides an obvious route for jihadists and would-be jihadists to entry the country. The problem of sham marriages is already significant and overlooked, but the risks are compounded further by the fiancé visa program.”

Nowrasteh believes that policy-makers need to put Malik’s situation in perspective.

“The K-1 visa is a fraction of a percent of the people coming into the U.S. on visas,” Nowrasteh said. “And to the best of my knowledge, this is the first one [K-1 recipient] to be involved with terrorism. I’d say that is a pretty good track record.”