WESTERN NORTH CAROLINA—The man who made the move to overthrow House Speaker John Boehner is back home now, shaking the hands of war veterans.

He grips the hands for so long, it’s like he is holding on for dear life.

As much as he is there for them, to reassure the veterans that their benefits are coming, they are here for him, to stand by a leader facing a consequential moment.

This is what happens when you risk it all—friends, money, power, respect—in the name of some greater purpose.

“What I’ve learned, is if you make promises to do your very best to fix something, it may cost you,” says Rep. Mark Meadows, speaking in a near-whispered southern drawl.

“It’s very easy to say you are willing to pay any cost. It’s a very different thing to actually be willing to go through and lay it all on the line. I for one — if it’s just me and me alone — I am willing to stand up and say this is what the people back home want, this is what they’re asking for, even if it makes it difficult on me in Washington D.C.”

Meadows says his controversial motion is “not personal between me and the speaker, but personal between me and the people I represent.” (Photo: Josh Siegel/The Daily Signal)

Meadows, a North Carolina Republican, made headlines in July when he presented a motion to vacate the chair, an extraordinary measure of no-confidence in the speaker of the House that hadn’t been used in a century.

During a normal day in his home district last week, which felt like a victory lap based on the warm reception of constituents, Meadows reflected on his decision with “no regrets.”

Indeed, when Congress returns from its six-week summer recess, Meadows warned he may take it a step further.

Meadows says if leadership’s tactics don’t change to his liking, he—or another supportive lawmaker—could refile the motion from “non-privileged to “privileged,” forcing a vote within two legislative days.

Meadows insists that Boehner would need to depend on Democrats to keep his speakership—he says there are “many more” than 29 Republicans who would vote to strip the speaker of his gavel (for comparison, 25 lawmakers did not vote to re-elect Boehner as speaker in January).

If the vote is successful, Meadows, for the first time, acknowledged that he would “certainly entertain” becoming speaker himself.

It’s a boast few would expect of Meadows, known as the soft-spoken representative of North Carolina’s 11th district, whose residents exist in a jungle paradise, among mountains that tint blue from far away.

Here, Meadows lives a decidedly normal life, in a home with unlocked doors, a doting wife, Debbie—the former Ms. Brandon (Florida) who he calls “hun”—and a three-and-a-half pound poodle.

Ambition to Rule

But in a way, Meadows’ actions make sense: he has a mean principled streak that has shown itself throughout his career.

Since Meadows was elected to Congress in 2012, the self-described “policy wonk” and “trivia guy” has made it a point to become an expert of the House’s complex rules.

“You’ve got to know about the rules to play by,” says Wayne King, Meadow’s district director.

“That’s where Mark has been very successful. He makes sure he plays by the rules and he doesn’t expect someone to tell him the rules. He will challenge people about the rules.”

On July 28, his birthday, Meadows used the rules as a weapon, when he introduced a resolution aimed at forcing Boehner from his post.

Meadows, who briefly lost his chairmanship of the Subcommittee on Government Operations for bucking party leaders on a procedural vote, says “we can’t be concerned about the cost of what is doing right.”

Believing that Boehner has presided over a caucus that has violated the Founding Fathers’ traditions, Meadows, beginning in March, worked with the House’s parliamentarian (a nonpartisan person who helps with rules), to find a remedy.

He learned about the motion to vacate, which had last been used in 1910 against then-Speaker Joseph Cannon, who refused to step down.

Meadows had planned to keep the tool at his side, as a worst case scenario, but he soon became more frustrated.

On June 20, Rep. Jason Chaffetz, R-Utah, removed Meadows from his chairmanship of the Subcommittee on Government Operations for voting against leadership on a normally routine procedural vote.

Meadows later regained his perch, but some of his colleagues were punished by House leaders for similar reasons.

Meadows felt compelled to go at it alone and author a starkly worded resolution stating that Boehner tried to “consolidate power and centralize decision-making.”

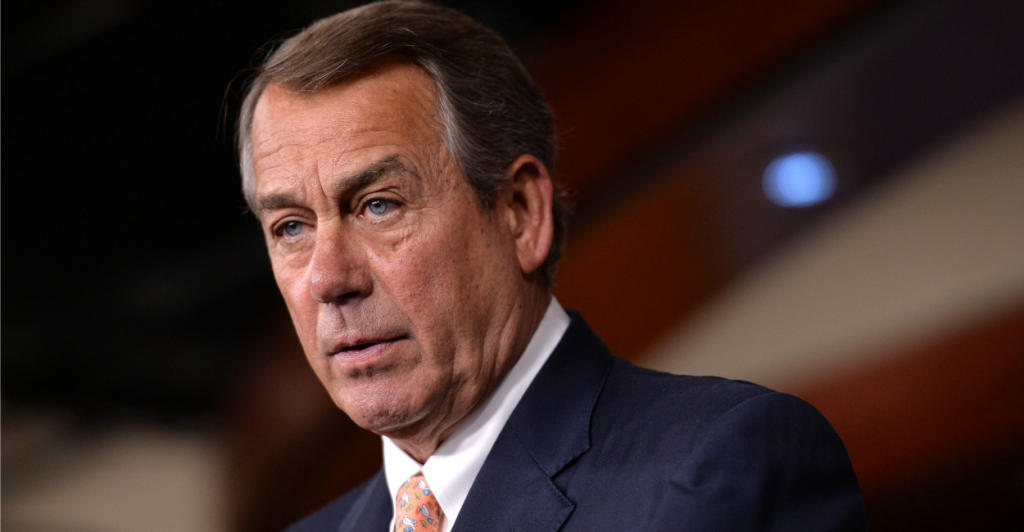

Supporters of House Speaker John Boehner says he has done his best to provide for an inclusive legislating process, while dealing with a fractured caucus. (Photo: Kevin Dietsch/UPI/Newscom)

Before he did it, Meadows sought the blessing of his family.

Days prior, his son, Blake, a law student at Emory University in Atlanta and his father’s reliable hunting partner, left Meadows a voicemail invoking Theodore Roosevelt and his effort to “make a difference, regardless of the outcome.”

“I told them [my family] if I did it, it may be a very lonely and difficult time — a time that quite honestly may send me back home,” Meadows says. “Whenever you go up against really established norms, it can be very costly personally. But they were all very supportive.”

In the end, the person Meadows surprised the most was himself. But maybe he should have known better.

“I didn’t know I had the intestinal fortitude to do it,” Meadows says. “You look at the consequences and it’s not an easy thing to do, especially for a guy who likes people. I do love people, so it makes it very difficult for me to really be the guy that is potentially not liked. I like to be liked. But I have no regrets. The person who stares back at me in the mirror is the same person as four years ago.”

‘Critical Time’

Those who know Meadows well insist his devotion is pure.

They say his seemingly competing two sides can be reconciled: the same normalness that makes him uncomfortable in the spotlight inspires him to stand up when he thinks the average person is wronged.

“He’s a great friend no matter what,” says Rep. Jim Jordan, R-Ohio, who along with Meadows and others founded the conservative House Freedom Caucus.

“I appreciate his perspective and outlook on life. He is also a great member of Congress. Countless Americans say we in Congress have forgotten about them. Mark is there to remember them.”

Rep. Jim Jordan, R-Ohio, says “no one does a better job” than Meadows at “digging into policy issues.” (Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call/Newscom)

Like it or not, Meadows has made his own life—and the day-to-day of the House Republican Conference—far from normal.

Most of his friends, even fellow House Freedom Caucus members, disagreed with Meadows’ decision to threaten Boehner, and even warned him against doing it.

Critics of the move say infighting and distractions are not what the Republican Party needs heading into a critical September, when lawmakers must confront key issues like the Iran nuclear deal, Planned Parenthood, and government funding.

“On a personal level, I have a good relationship with Mark Meadows, but his motion was clearly not well thought-out,” says Rep. Charlie Dent, R-Pa., who adds the issue has not come up during town halls with constituents over recess. “It’s a distraction from other issues on the agenda. And I respectfully disagree with what the resolution says. Speaker Boehner has allowed for a more open, inclusive process than any speaker during my 11 years in Congress.”

Meadows argues the coming issues deserve strict scrutiny, and that his motion to vacate served as a warning shot for House leadership to include people like him in the discussion.

“It is a critical time for our leadership to listen to the American people,” Meadows says.

“There was no more important message to me than that. Really, it is not as important for me to get a new speaker, as it is to get the speaker to respond to those he is elected to serve—that is, members of Congress. If we have a leadership that becomes responsive, then nothing happens with the resolution. If they are not responsive, the only thing we can change at this particular point is the speaker of the House, and then that certainly is on the table.”

‘Send Me Home’

Meadows also faces a fight to retain his own House seat, which he admits is very much in doubt.

Meadows says that before 5 p.m. on the day after he submitted his controversial motion, his Washington, D.C., fundraiser “fired him.”

He shares this proudly and unprompted, with a slight chuckle.

“He was very nice about it,” Meadows recalls. “He just said I can’t raise any more money in this town for you because of what you just did. We haven’t replaced him. We are still evaluating who might possibly would want to take on that herculean task.”

Meadows also faces challenges closer to home.

Meadows presents a $153,881 grant from the Federal Emergency Management Agency to George Hildebran Fire and Rescue. “We got your back,” Meadows says. (Photo: Josh Siegel/The Daily Signal)

As the North Carolina Supreme Court prepares to hear arguments in a gerrymandering lawsuit, some have speculated the state legislature could redraw its congressional districts.

If that were to happen, Meadows’ reliably conservative district may become less so.

“Redistricting is not something I am concerned about,” Meadows insists. “If they do make it less conservative, that’s making the assumption that the state legislature is going to adhere to the wishes of Washington D.C. And knowing some of the folks involved, I know most of them are their own people.”

Nothing ‘Special’

Three weeks to the day after he became the person to offer the most serious challenge to Boehner’s speakership, Meadows spontaneously invites two cops for lunch at 12 Bones Smokehouse in Arden, N.C.

He asks more questions of his guests than they do of him.

“You get some of those Obama beans?” Meadows says, laughing at his own joke about the president’s known affection for this very restaurant (Obama ate here during his 2008 campaign for president, so this place is a bipartisan affair).

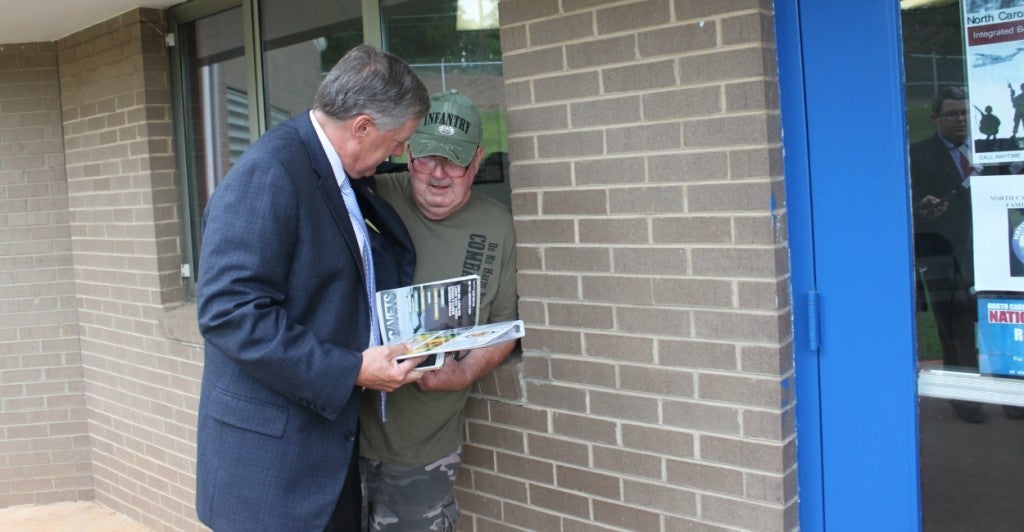

Meadows, sharing a moment with a veteran in Marion, N.C., is the son of a military father and was born at a U.S. Army hospital in Verdun, France. (Photo: Josh Siegel/The Daily Signal)

At two veterans events, Meadows will not leave until he greets every man and woman he sees, and he will convert some detail about each of them to memory.

“I get my energy from other people,” Meadows says.

“But as much as I like people, I can be perfectly content sitting alone reading policy issues. Since the motion to vacate, there has been a lot more attention on me than I would care to have. As long as they don’t think there is anything special about me, I am okay with that. I am still a guy who grew up with very humble beginnings.”

‘Put This Area on the Map’

The dissatisfaction of constituents like Shurman Surrett is what inspired Meadows to act.

“I am living on these two batteries pumping my blood, and I am tired,” says Surrett, surviving with the aid of a heart pump attached to his hips after battling cancer and other health problems.

Surrett, a 69-year-old Vietnam War veteran, is proudly and stubbornly conservative, typical of the 11th district.

Before Meadows was elected, redistricting made the district the most conservative in the state.

Attending a Veterans Affairs seminar in Waynesville last week, Surrett whispered into Meadows’ ear, “Thanks for standing up to Boehner.”

“Boehner is not the conservative that I am, that Mark Meadows is,” Surrett says. “We’ve got Meadows’ back. I just think he’s a standup guy. He’s been standing alone there for awhile.”

Shurman and Margaret Surrett of Canton, N.C., believe their congressman, Mark Meadows, is the “only good guy left in Washington D.C.” (Photo: Josh Siegel/The Daily Signal)

Another attendee of the seminar, Al Goodis, 78, a veteran of the Navy, is similarly proud of Meadows.

“He has put this area on the map,” says Goodis, whose t-shirt is covered by Ronald Reagan’s face and the message, “The best social program is a job.”

After the event, Meadows says he’s surprised by the support since Waynesville belongs to one of the more liberal counties in his district.

The faith convinces Meadows he made the right move, and bolsters his formula as a lawmaker: vote how your people want you to.

“People who disagree with me don’t know the support I have back home,” Meadows says. “The displeasure and difficulty this decision created with some of my colleagues is hard to hear. I truly love 99 percent of the people I serve with and I respect them greatly. But my word to the people that I represent is a lot stronger than that.”

Barbara Buck, 81, and Al Goodis, 78, appearing at a Veterans Affairs seminar in Waynesville, N.C., offered support to Meadows for “standing alone” to challenge Boehner.

On this regular day in the district—which is so large it takes five-and-half hours of driving on Smokey Mountain Expressway to get through—Meadows is there to say thanks.

During a visit of a car dealership, Sunset Chevrolet, Meadows bumps shoulders to avoid the dirty hands of mechanics and promises the owner of the place that he will help “cut through the red tape and make it easier for you.”

“I worked on commission most of my life,” Meadows relates to the Chevy staff. “If I didn’t perform, I didn’t eat.”

Later, Meadows takes the pulse of law enforcement leaders who have gathered at McDowell County Sheriff’s Office.

Some of the 17 sheriffs in Meadows’ district shared with him their skepticism over federally-mandated body cameras for police. Several recent high-profile police shootings of civilians have created bipartisan momentum for cops to wear cameras that could capture use-of-force events as they happen.

Meadows says he had been leaning towards supporting legislation that would require that, but his conversation with the sheriffs made him reconsider.

“If that’s where they are on it, that’s where I will be,” Meadows says.

“I learned a long time ago that if I side with law enforcement, I am right 99.9 percent of the time. Until they show me a reason I can’t trust them, I am relying on them.”

Meadows’ district is 91 percent white, rural and low crime.

When a reporter asked Meadows if the loyalty to his own could prevent him from voting in a way that would benefit the broader country, he gave no doubts of his priorities.

“I make my policy decisions based on how my constituents view it as good or bad,” says Meadows, who recalls three or four times in his career where he’s voted against the wishes of constituents. “The only time I will go against them, is if it is a moral belief. I got their back.”

In this place, Meadows is fine exactly where he is.

“How do I speak to Mark Meadows being the one?” he says of his unlikely position.

“History is full of people who they said were nothing more than business guys and fathers and farmers, but who are there to stand up for what they believe in,” Meadows continues. “So I don’t see my name going down in history as a great leader. I’m just a willing participant trying to voice the concern of millions of Americans across the United States.”

“If that gets me in trouble,” he says, “the worst thing is they send me home to the beautiful mountains of western North Carolina, where the vast majority of people still love and appreciate someone who is willing to stand on principle.”