Today, the U.S. Census Bureau will release its annual report on poverty. This report is noteworthy because this year marks the 50th anniversary of President Lyndon Johnson’s launch of the War on Poverty. Liberals claim that the War on Poverty has failed because we didn’t spend enough money. Their answer is just to spend more. But the facts show otherwise.

>>> Full Report: The War on Poverty After 50 Years

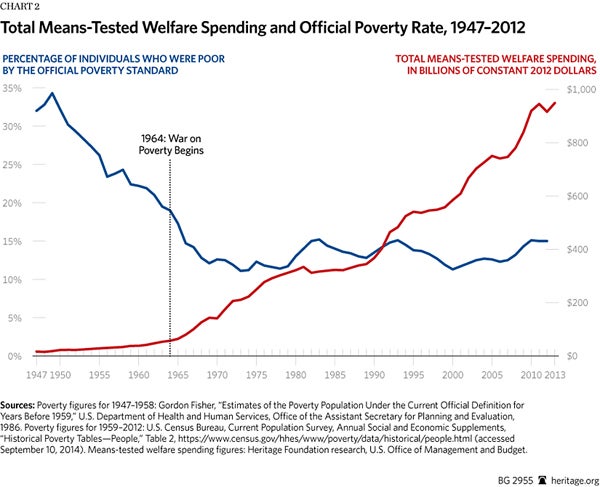

Since its beginning, U.S. taxpayers have spent $22 trillion on Johnson’s War on Poverty (in constant 2012 dollars). Adjusting for inflation, that’s three times more than was spent on all military wars since the American Revolution.

One third of the U.S. population received aid from at least one welfare program at an average cost of $9,000 per recipient in 2013.

The federal government currently runs more than 80 means-tested welfare programs. These programs provide cash, food, housing and medical care to low-income Americans. Federal and state spending on these programs last year was $943 billion. (These figures do not include Social Security, Medicare, or Unemployment Insurance.)

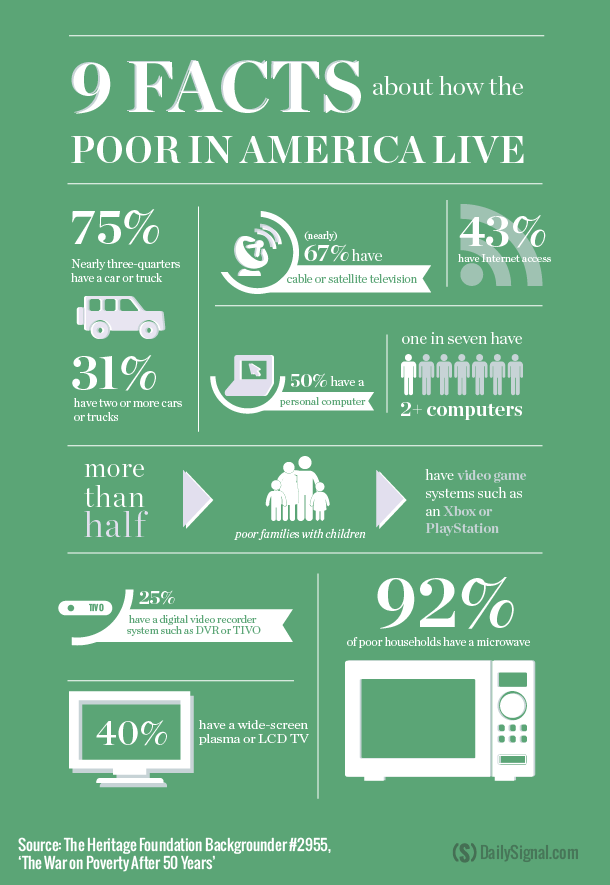

>>> INFOGRAPHIC: 9 Facts About How the Poor in America Live

Over 100 million people, about one third of the U.S. population, received aid from at least one welfare program at an average cost of $9,000 per recipient in 2013. If converted into cash, current means-tested spending is five times the amount needed to eliminate all poverty in the U.S.

But today the Census will almost certainly proclaim that around 14 percent of Americans are still poor. The present poverty rate is almost exactly the same as it was in 1967 a few years after the War on Poverty started. Census data actually shows that poverty has gotten worse over the last 40 years.

How is this possible? How can the taxpayers spend $22 trillion on welfare while poverty gets worse?

The typical family that Census identifies as poor has air conditioning, cable or satellite TV, and a computer in its home.

The answer is it isn’t possible. Census counts a family as poor if its income falls below specified thresholds. But in counting family “income,” Census ignores nearly the entire $943 billion welfare state.

For most Americans, the word “poverty” means significant material deprivation, an inability to provide a family with adequate nutritious food, reasonable shelter and clothing. But only a small portion of the more than 40 million people labelled as poor by Census fit that description.

The media frequently associate the idea of poverty with being homeless. But less than two percent of the poor are homeless. Only one in ten live in mobile homes. The typical house or apartment of the poor is in good repair and uncrowded; it is actually larger than the average dwelling of non-poor French, Germans or English.

According to government surveys, the typical family that Census identifies as poor has air conditioning, cable or satellite TV, and a computer in his home. Forty percent have a wide screen HDTV and another 40 percent have internet access. Three quarters of the poor own a car and roughly a third have two or more cars. (These numbers are not the result of the current bad economy pushing middle class families into poverty; instead, they reflect a steady improvement in living conditions among the poor for many decades.)

The intake of protein, vitamins and minerals by poor children is virtually identical with upper middle class kids. According to surveys by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the overwhelming majority of poor people report they were not hungry even for a single day during the prior year.

We can be grateful that the living standards of all Americans, including the poor, have risen in the past half century, but the War on Poverty has not succeeded according to Johnson’s original goal. Johnson’s aim was not to prop up living standards by making more and more people dependent on an ever larger welfare state. Instead, Johnson sought to increase self-sufficiency, the ability of a family to support itself out of poverty without dependence on welfare aid. Johnson asserted that the War on Poverty would actually shrink the welfare rolls and transform the poor from “taxeaters” into “taxpayers.”

Judged by that standard, the War on Poverty has been a colossal flop. The welfare state has undermined self-sufficiency by discouraging work and penalizing marriage. When the War on Poverty began seven percent of children were born outside marriage. Today, 42 percent of children are. By eroding marriage, the welfare state has made many Americans less capable of self-support than they were when the War on Poverty began.

President Obama plans to spend $13 trillion dollars on means-tested welfare over the next decade. Most of this spending will flow through traditional welfare programs that discourage the keys to self-sufficiency: work and marriage.

Rather than doubling down on the mistakes of the past, we should restructure the welfare state around Johnson’s original goal: increasing Americans capacity for self-support. Welfare should no longer be a one way hand out; able-bodied recipients of cash, food and housing should be required to work or prepare for work as condition of receiving aid. Welfare’s penalties against marriage should be reduced. By returning to the original vision of aiding the poor to aid themselves, we can begin, in Johnson’s words, to “replace their despair with opportunity.”