Bailouts Could Be More Than 35 Times State Revenue Losses

Adam Michel /

The most recent compromise proposal floated in the coronavirus aid negotiations would send another $250 billion to state and local governments. More state bailouts are unnecessary and harmful to the economic recovery. Not to mention a waste of future taxpayers’ hard-earned money.

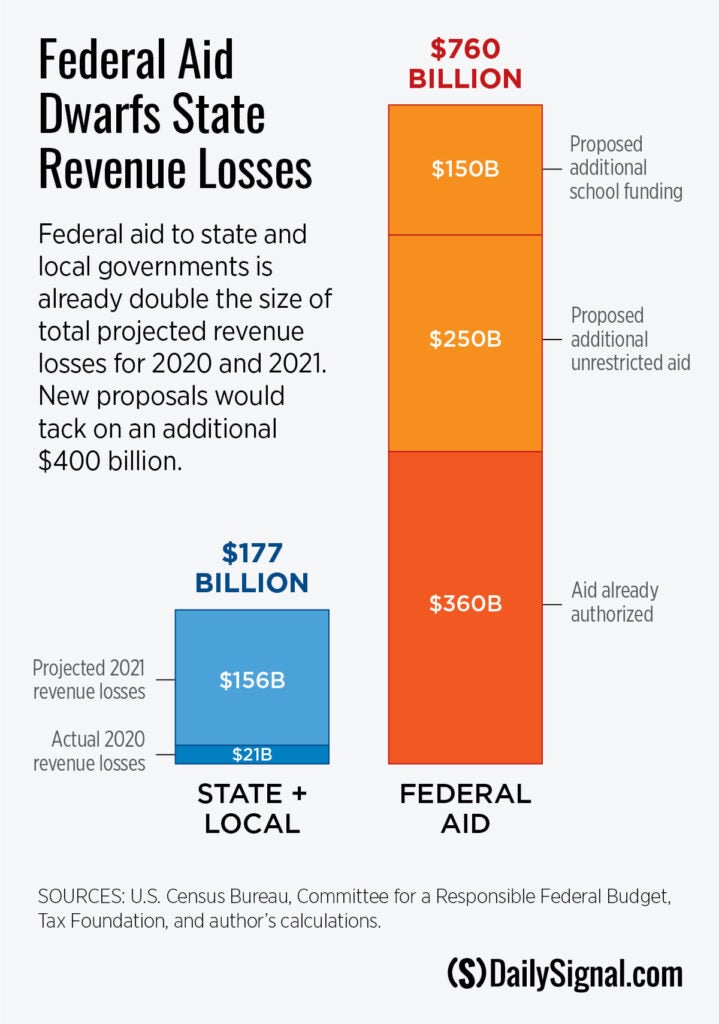

The federal response to the COVID-19 pandemic has already provided $360 billion to state and local governments in direct aid to cover costs of coronavirus spread and containment, increased Medicaid funding, support for education systems, child care for front-line workers, and subsidies for mass transit systems.

In the meantime, state revenues have fared much better than most predictions. State and local revenues only declined by 1.4% in fiscal year 2020, which ended in June. That is a $21 billion revenue loss compared to 2019, according to preliminary non-seasonally adjusted Census data.

The most recent state aid proposal floated in the congressional negotiations, in addition to existing bailouts, would be 35 times larger than this year’s revenue loss.

Democrats passed their own $2.2 trillion bill along party lines on Thursday to try to force negotiations. The Democrats’ bill would send an additional $661 billion to the states, a full 48 times state and local 2020 revenue losses.

These proposals represent an attempt to inflate state budgets beyond any reasonable measures of actual need.

Federal state and local aid already authorized by Congress is 16 times larger than their 2020 revenue loss and two times larger than their expected 2020 and 2021 combined losses.

If Congress authorizes an additional $250 billion in unrestricted bailouts and $150 billion for state school budgets, it will replace 428% of state and local projected revenue declines for 2020 and 2021.

Many states also entered this crisis with well-funded rainy day accounts. At the end of 2019, state rainy day funds contained $75.5 billion, which could cover 8.7% of annual expenditures.

Because some local revenue sources aren’t fully included in the Census data, it is also helpful to look at state-only revenues, which declined by $59 billion or 5.5%.

However, state-only data is also an incomplete picture because local revenues are much more stable than state revenues and delayed income tax fillings due to the pandemic make losses look larger than they will be once tax filings have caught up.

Existing unprecedented federal aid has already made sure that most states are not short on funds. In fact, data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis confirms that state and local governments had a surplus of more than $100 billion in the final quarter of the 2020 fiscal year.

However, states that chose to not fund their rainy day accounts that have been particularly hard hit by health crisis or have maintained overly burdensome economic restrictions may still find themselves tight on cash.

In these limited cases, states have many budgetary options to constrain cost growth that are normal in the private sector. A one-year pay freeze, for example, could save states about $50 billion, and suspending pension contributions and accruals for one year could save up to $234 billion.

These reforms would go a long way toward stabilizing state budgets without cutting crucial services or instituting mass layoffs. Such changes would require renegotiating public employee contracts, but state and local workers would probably prefer to forgo a pay raise or a year’s pension contributions instead of losing their job.

Bailing out state and local budgets is also not a safeguard against state tax hikes. When temporary federal money runs out, states have historically increased taxes permanently to make up the difference. Each dollar of federal grant money has historically resulted in 40 cents of state and local tax increases.

Federal aid actually tends to expand state budgets and make them less resilient during future crises, perpetuating problems like systematic underfunding.

Federal subsidies also undermine local decision-making about the best path for reopening and set a dangerous precedent that could lead to trillions of dollars in additional federal bailouts of the most irresponsible states and local pension systems.

States’ budgets should be their own responsibilities. Shifting resources from taxpayers in responsible states that were better prepared for shortfalls and that have enacted budget cuts to irresponsible states that didn’t save and have refused to adjust their budgets would encourage fiscal recklessness in the future.

It certainly also doesn’t make sense for the federal government to assume state and local shortfalls when it already has about seven times as much debt per capita as state and local governments.

Instead of aiding the recovery and encouraging responsible budgeting, additional federal state bailouts would likely delay economic recovery, cause blatant inequities, and result in higher costs for everyone.