Ukraine’s Soviet-Era Space Program Boosts a US Commercial Spaceflight Company’s Chances for Liftoff

Nolan Peterson /

DNIPRO, Ukraine—From a 15th-floor balcony overlooking this city’s Yuri Gagarin Park, American John Isella looks east beyond the skyline toward the Dnieper River. A forested expanse stretches to the horizon in the direction of the war, about four hours away by car if you wanted to drive there.

“It’s hard to believe the war is so close,” Isella, 61, says.

A former NASA engineer, Isella lives in Ukraine full time as the director of international business development for Firefly Aerospace, an American commercial spaceflight company.

On the factory floor at Firefly’s research and development center in Dnipro. (Photos: Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

Headquartered in Cedar Park, Texas, Firefly Aerospace is owned by a 41-year-old Ukrainian entrepreneur named Max Polyakov whose vision is to leverage the legacy of Ukraine’s Soviet space program to usher in a new era of more affordable commercial spaceflight ventures.

“We’re not talking about going to Mars,” Isella says. “We want a commercially successful business.”

On this day, we’re at Firefly Aerospace’s Dnipro headquarters. It’s on Gagarin Avenue in downtown Dnipro.

The company shares the top floors of a modern office building with a nonprofit organization called Noosphere—also owned by Polyakov—which supports high-tech innovators and enterprises in 17 countries.

Bespectacled and soft-spoken, Isella’s emotionally moderated demeanor is what you’d expect from a systems engineer who, over the course of an eclectic career, has worked on projects spanning the gamut from the Hubble Space Telescope to classified Department of Defense programs.

Yet, the passion in Isella’s voice is clear when he talks about space.

“It’s fascinating to be in a position in this industry to watch things really take off—so to speak,” Isella says, cracking a grin.

Standing beside Isella on the panoramic balcony is Michael Ryabokon, the chief operating officer for Noosphere Ventures—Noosphere’s venture capital branch.

With short-cropped blond hair and a solid build, Ryabokon is outspoken and effusively enthusiastic about the future of Ukraine’s high-tech industries like space flight and robotics. A former Ukrainian army artillery officer, he has a penchant for whisky and cigars and all things military. He’s also deeply patriotic.

“Ukraine has a lot of reasons to be proud,” Ryabokon says. “We’re building a better future for ourselves.”

Ryabokon points to an array of massive metal towers, which interrupt Dnipro’s industrial skyline. During the Cold War, Ryabokon explains, the towers were used to jam electromagnetic signals.

“America was the enemy, then,” Ryabokon says. “Now, Russia is the enemy and America is our friend. Times have changed, huh?”

“This was the heart of the evil empire,” Isella adds with a wry grin, referencing former U.S. President Ronald Reagan’s famous characterization of the Soviet Union.

For Firefly’s Soviet space program veterans, who form the backbone of its burgeoning operations in Ukraine, working for an American commercial spaceflight company would have been unimaginable during the Soviet era, when Ukraine’s space program was a state secret of the highest order.

For their part, Ukraine’s up-and-coming millennial generation of spaceflight innovators sees the commercial spaceflight industry as a potential economic boon to their country. But, more importantly, they want to inspire the Ukrainian people, who’ve lived amid the backdrop of revolution and war for more than four years.

“Ukraine needs a success story,” Isella says. “And this is it.”

Closed City

Spread across the west bank of the Dnieper River in central Ukraine, Dnipro is an industrial city of about 1 million people. Roughly 40 percent of the Soviet Union’s space program industry was located in Dnipro during the Cold War. It’s where Soviet engineers designed and built rockets such as the Satan intercontinental ballistic missile, which was designed to strike the United States with nuclear weapons.

During the Soviet era, the spaceflight secrets locked away in Dnipro were important enough that the Kremlin designated it a “closed city.” No foreigners were allowed in, and Soviet citizens needed a special permit to visit.

Today, Dnipro’s role in the Soviet space program remains a rare piece of Soviet history Ukrainians choose to embrace and celebrate, rather than forget.

In April 1961, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin was the first man in space, beating the American Alan Shepard by three weeks. Along with other historic spaceflight achievements like the Sputnik satellite launch in 1957, the Soviet space program was an indelible source of pride for Soviet citizens in the decades following the apocalyptic toll of World War II.

(Official estimates vary, but roughly 8 million Ukrainians died in the war from 1941 to 1945. That number represents roughly 20 percent of Ukraine’s pre-war population of 41.7 million people.)

Today, Ukraine is at war once again.

After more than four years of nonstop combat, Ukrainian troops remain hunkered down in trenches and ad hoc forts along a 250-mile-long front line in the country’s embattled, southeastern Donbas region. There, Ukraine’s military continues to fight a grinding, static war against a combined force of pro-Russian separatists and Russian regulars.

Every day in Ukraine’s embattled Donbas region, artillery still thunders in a trench war that has, so far, killed more than 10,300 Ukrainians and continues to claim the life of one Ukrainian soldier every three days.

The conflict has spurred a Ukrainian cultural divorce from Russia. To that end, in 2015, Ukraine outlawed all symbols and relics of the Soviet Union. Since then, all the remaining statues of Vladimir Lenin have come down. It’s now illegal to display the hammer and sickle flag or to play the Soviet national anthem. All Soviet names were also replaced. For its part, the city once known as Dnipropetrovsk was renamed to today’s “Dnipro”—the excised “petrovsk” referred to Communist leader Grigory Petrovsky.

Despite the cultural purge of all things Soviet, Ukrainians see their country’s Soviet space program heritage through a more positive lens than other artifacts of their Soviet past. Today, with all the statues of Lenin reduced to empty pedestals, Dnipro’s Gagarin Avenue and Yuri Gagarin Park still retain their Soviet-era names.

Similarly, when it comes to Ukraine’s future, its burgeoning commercial space flight industry is a uniquely powerful symbol of progress.

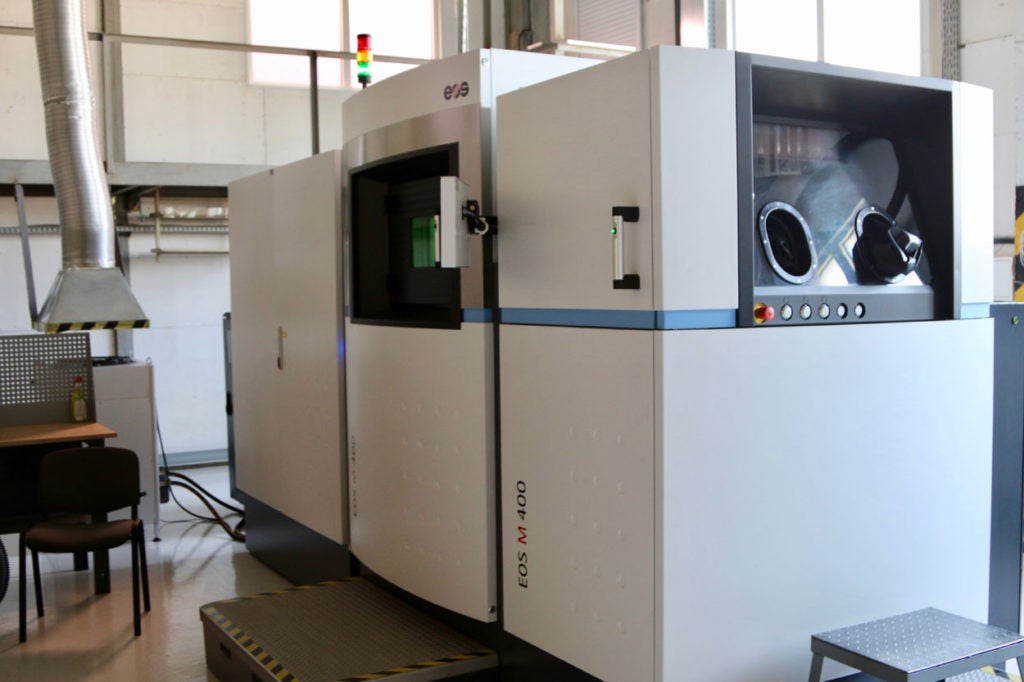

For his part, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko was on hand to celebrate the opening of Firefly’s Dnipro facility in May. At the site, Firefly’s researchers—many of whom are veterans of the Soviet space program—are now testing ways of mass-producing rocket components with 3D printers.

That innovative manufacturing process is part of what sets Firefly’s business plan apart from those of other commercial spaceflight ventures, such as SpaceX.

Rather than focusing on grandiose projects like colonizing Mars or building rockets to rival NASA’s Saturn V moonshot behemoths, Firefly’s mission is to “provide economical, high-performance space launch capability for the underserved small satellite market, where secondary-payload launches are often the only option.”

A secondary payload refers to a small satellite that piggybacks on a larger orbital delivery to get to space with its own dedicated launch vehicle.

In short, Firefly is focused on building and launching smaller rockets that will launch smaller satellites. And it wants to build them cheaper than the competition. Part of Firefly’s price advantage comes from building its manufacturing base in Ukraine.

“In terms of rocketry, nothing we’re doing is revolutionary,” Isella says. “The advancements that we’re making, more evolutionary than revolutionary, are in manufacturing—making the rocket production more financially sound, more profitable.”

Over the Goal Line

Currently, Firefly has two rockets under active development.

The Firefly Alpha is a liquid oxygen-fueled rocket, which will deliver a payload of up to 2,205 pounds to low-earth orbit, or about 1,320 pounds to a sun-synchronous orbit.

(The altitude for low-earth orbit is at about 125 miles; for sun-synchronous orbits it’s about 310 miles.)

The Firefly Beta, which is at the prototype stage, is intended to link several Firefly Alpha boosters into one rocket stack. Altogether, the Firefly Beta should be able to deliver an 8,818-pound payload to low-earth orbit, or about 6,600 pounds to sun-synchronous orbit.

As a point of comparison, SpaceX’s workhorse Falcon 9 rocket can put up a payload of 50,265 pounds to low-earth orbit. And, according to SpaceX’s website, it can propel an 8,860-pound payload to Mars.

“Small to medium rockets are a market segment that’s currently underserved,” Isella says. “We’re not pushing the limits of technology. We’re a business.”

“Now, the real drivers in the space industry are the constellation concepts,” Isella continues. “That means smaller spacecraft, and more of them. Many small satellites can provide full coverage of the earth from specific orbits.”

Another space industry trend has been in the consumer’s growing appetite for data analytics.

With that in mind, a geo-analysis software project called EOS—another Noosphere venture—will be melded with the launch operations of Firefly. It will be a synergistic effort between the orbital software and the launch hardware, personnel say.

At Firefly they call it “full integration”—fusing the data-analytics arm of the company with the launch technology end. The concept is a bellwether for the future of the commercial space industry business model, Isella says.

“It will be a really aggressive offering in the marketplace as far as affordability goes,” Isella says. “We’re not just building rockets, we’re not just building spacecraft. It’s about fully integrating the data analytics piece, too. That’s what the consumer wants.”

In the short term, Firefly’s goal is to begin launching its Alpha and Beta rockets at a rate of twice a month by 2021. Further down the line, it has plans for a reusable rocket called Gamma.

The U.S. Air Force granted Firefly preliminary approval to use the former Delta launch facilities at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California—saving the company two years and $150 million by foregoing the need to build its own launch site.

“All we have to do is adapt the existing infrastructure to our rockets. It will just take months,” Isella says.

To date, Firefly has secured 10 letters of intent to purchase its rockets. The first launch of the Alpha rocket is tentatively scheduled for 2019.

Red Tape

The Firefly manufacturing facility in Dnipro isn’t much to look at on the outside. It matches the weathered look of many buildings in Dnipro’s industrial environs.

Inside, however, it’s an altogether different story.

The factory floor is a noisy frenzy of nonstop activity as the workers, all 120 of them, purposefully execute their myriad tasks. Most of the 3D printers they operate are about the size of a Volkswagen Beetle—some are as large as a Winnebago. On this day, all the printers seem to be up and running.

“We’re combining American rocket skills and Soviet rocket skills, and no one has done that before,” says Yuriy Zabiyaka, CEO for Firefly Ukraine.

Among the older engineers and factory workers who used to work for the Soviet space program, you see echoes of both the pride and the paranoia of the Soviet era.

They tend to hunch a little closer to their computer screens, concealing what’s on them, as this American correspondent walks past. For the most part, they don’t overtly acknowledge an outsider’s presence, yet you get the sense that they’re always aware of your location, and what you’re looking at.

Technically, Firefly Ukraine is a separate company from its American counterpart. Therefore, Firefly Ukraine is subject to restrictive U.S. trade laws when it comes to rocket technology.

Firefly’s rockets fall under the U.S. government’s International Traffic in Arms Regulations, or ITAR—meaning the technology is classified by the U.S. State Department as militarily sensitive and its dissemination to foreign countries is limited.

“Missile technology is highly controlled,” Isella says.

The ITAR laws are meant to prevent U.S. military technology from ending up in the wrong hands. For that reason, under U.S. law, Firefly’s American arm is prohibited from sharing any technical information with Firefly Ukraine until a Technical Assistance Agreement, or TAA, is approved by the State Department.

The TAA is basically a rulebook for sharing information, which the State Department has to approve before Firefly’s U.S. operation can share any information with its Ukrainian outpost.

According to company personnel, Firefly Ukraine is the first non-U.S. company to ever apply for a TAA.

But there’s a catch.

In order to get the TAA approved, Firefly has to build its entire Ukrainian infrastructure, including a fully functional manufacturing facility.

“We have to have the company set up and running here before the U.S. will give us approval,” Isella says. “So, the facilities are built, and we’re ready to kick-start the production lines when, hopefully, the TAA is approved.”

“If we get the TAA then by the end of the year we can deliver our first big components to the U.S.,” says Zabiyaka, Firefly Ukraine’s CEO.

But the TAA pickle makes rocket development more difficult.

Firefly’s engineers in Texas aren’t allowed to tell their Ukrainian counterparts what parts they’ll need, leaving Firefly Ukraine’s Soviet space veterans to rely on their professional experience to anticipate what parts the rockets will need.

At this point, the Ukrainians are experimenting with the 3D printing technology and working out the kinks in the manufacturing process so that when the TAA is finally approved, they can immediately kick-start the mass production of rocket components.

“We’re experimenting to see what we can do,” Zabiyaka says, adding:

But until the TAA is approved, Firefly Ukraine operates independently. The U.S. side can’t send us materials for testing, and we can’t collaborate with them at all. We can send information to the U.S., but the U.S. side can’t respond. It’s a one-way street. But we need feedback to make the proper components for the rockets.

As of this article’s publication, Firefly’s TAA application is in the final phase of review.

Meanwhile, the pending decision looms over the factory floor in Dnipro like a background static charge about to arc.

“If we don’t get the TAA, then what we’re doing here is useless,” Zabiyaka says. “Everyone is waiting for the next step. We’re all nervous. We try to believe there’s a future here.”

Amid the backdrop of the activity on the factory floor, Zabiyaka pauses to study a mockup of Firefly’s Beta rocket.

“I think a lot of people still think this is all too good to be true,” Zabiyaka says. “But, if the Ukrainian people see a Ukrainian flag and a U.S. flag on the side of a rocket lifting off into space, it would be very inspiring.”

Evolution

In Dnipro, Firefly isn’t the only commercial spaceflight startup in town. A 2-year-old company called Space Electric Thruster Systems, or SETS, is designing cutting-edge electro-propulsion space thrusters for satellites.

“We’re trying to find new ways to build thrusters at a low cost,” says Viktor Serbin, the founder and CEO of SETS. “We’re taking students from university and rebuilding the electro-propulsion community here in Ukraine.”

Asked how he keeps costs low, Serbin smiles and says, “We’re in Ukraine.”

Fair-haired and with a smile permanently affixed to his face, Serbin worked at Ukraine’s state-run Yuzhmash rocket construction company for five years before joining SETS. He says leftover Soviet bureaucratic malaise has stifled Ukraine’s modern state-run space program.

“It’s difficult to work there, if you’re talking about their mentality,” Serbin says, describing the Yuzhmash bureaucracy. “Maybe, sometimes, people want to change something,” he adds, “but it’s difficult to change things. It’s like a big whale trying to turn.”

Like Firefly, SETS belongs to the Noosphere organization.The company’s Dnipro workshop has the feel of a Silicon Valley startup. The desks don’t have dividers. The team is an eclectic mix of fresh university graduates and veterans of the Soviet space program. They’re all dressed casually and their demeanor is relaxed. Some younger personnel have earbuds in as they work, their heads bobbing to the music.

The laid back work environment reflects Serbin’s leadership vision. His idea is to use Soviet-era spaceflight know-how—but to ditch the Soviet-era mentality.

“I believe in the future we can do something different, we can change the way things are done in our country,” Serbin says. “But it’s tough sometimes to remove people from this Soviet mentality, so it’s very important to have the right climate in here. We’re trying to think differently.”

“We broke with the Soviet mode of thinking,” says Olexandr Petrenko, a professor of astronautical engineering and a veteran of the Soviet space program who is chief technology officer for SETS.

“We’re a big family,” Petrenko adds. “And our main goal is to fly in space.”

Electro-propulsion is a means of thrust that can operate in the vacuum of space, where there is no available oxygen to fuel combustion. Electro-propulsion thrusters are smaller and use less fuel than other orbital thrusters. Therefore, Serbin says, the technology can extend the current orbital lifespan of geostationary satellites to 21 years, up from the current number of about 12 to 17 years.

NASA expects the number of satellites with electric thrust will increase by 30 percent within 10 years, Serbin explains.

Serbin and Petrenko stand back to proudly observe as they demonstrate one of their electro-propulsion thrusters for this correspondent. Inside a vacuum tube, the thruster silently emits a purple plasma cone. Admittedly, it’s beautiful and impressive.

SETS’ thrusters are still in the design phase, but Serbin anticipates they’ll be ready for spaceflight around spring of 2019. And his team is working tirelessly to that end.

“If you come here on a Saturday, 80 percent of my guys will be here,” Serbin says. “I tell them to go on vacation, but they won’t listen.”

This correspondent asks what the source of motivation is for such a relentless work ethic.

“They like the work, and the mission,” Serbin says. Then, as is his habit, he smiles broadly and adds, “And they love the dream.”

“What dream?” this correspondent asks.

“That something they build will actually fly in space,” Serbin replies.