This Ukrainian Regiment Began With Civilian Volunteers. Now It’s Going Pro.

Nolan Peterson /

URZUF, Ukraine—At the Azov Regiment’s base in this beach resort town on the Sea of Azov coast, you can sometimes hear the sounds of shelling from the front lines, which are about 42 miles east of here, toward the Russian border.

Yet, on this blustery summer day in late August, tourists are out swimming on the public beach down below the military base—even though it’s a little cold out and there’s a war 45 minutes away by car. Even in war, after all, life goes on. Those intrepid tourists are enjoying the last few days of summer before students go back to school on Sept. 1.

As summer fades to a close before the new school year, the war was also supposed to end on Sept. 1 as part of a “back to school” cease-fire recommitment. After more than three years of constant combat, such agreements have become an annual farce. Few believe this latest peace deal will last. Certainly not the Azov Regiment soldiers deployed here on the edge of the war zone.

Chris Garrett, a British army veteran, who has been with the Azov Regiment since 2014. (Photos: Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

“Nobody thinks this cease-fire is gonna help anyone because almost all cease-fires have not worked as they should,” Anton Kolomoets, a soldier in the Azov Regiment, told The Daily Signal on a recent visit to the unit’s Urzuf base.

“Most of the guys hope that this war will end with us taking control of the Ukrainian border, and taking back Luhansk and Donetsk. So nobody likes the idea of ‘cooling off,’” Kolomoets said, referring to the capital cities of the two Russian-backed separatist territories in eastern Ukraine.

“It’s not so intense right now, but after the first of September, we think it will get worse again,” an Azov Regiment soldier who went by the nom de guerre “Nikopol” told The Daily Signal. “We don’t believe the war will end soon.”

(Due to security concerns, some Azov Regiment soldiers requested that their full names be withheld.)

Common Cause

In 2014 the Azov Regiment took over a seaside villa in Urzuf that belonged to Viktor Yanukovych, Ukraine’s former pro-Russian president who was overthrown during the February 2014 pro-Western revolution. Predictably and tellingly, the deposed president fled to Russia where he now lives in exile.

Yanukovych’s vacated holiday getaway in Urzuf has since become the Azov Regiment’s main war zone hub.

The Azov Regiment was created in Spring 2014 as the Azov Battalion. It began as an extra-governmental civilian volunteer paramilitary unit—a militarized offshoot of protest groups active during the 2014 revolution. In the beginning, Azov’s troops scrounged together whatever weapons they could find and rushed off to the front lines with practically no training (except for some military veterans in their midst) and a fluid command hierarchy.

Soldiers described that early time as “natural selection” boot camp. Survival on the battlefield was the right of passage. It was a do or die moment for Ukraine. With the regular army on its heels as Russia’s proxies leapfrogged across southeastern Ukraine, ad hoc, partisan groups like Azov ultimately turned the tide of the war and effectively prevented Russia from cleaving Ukraine in two.

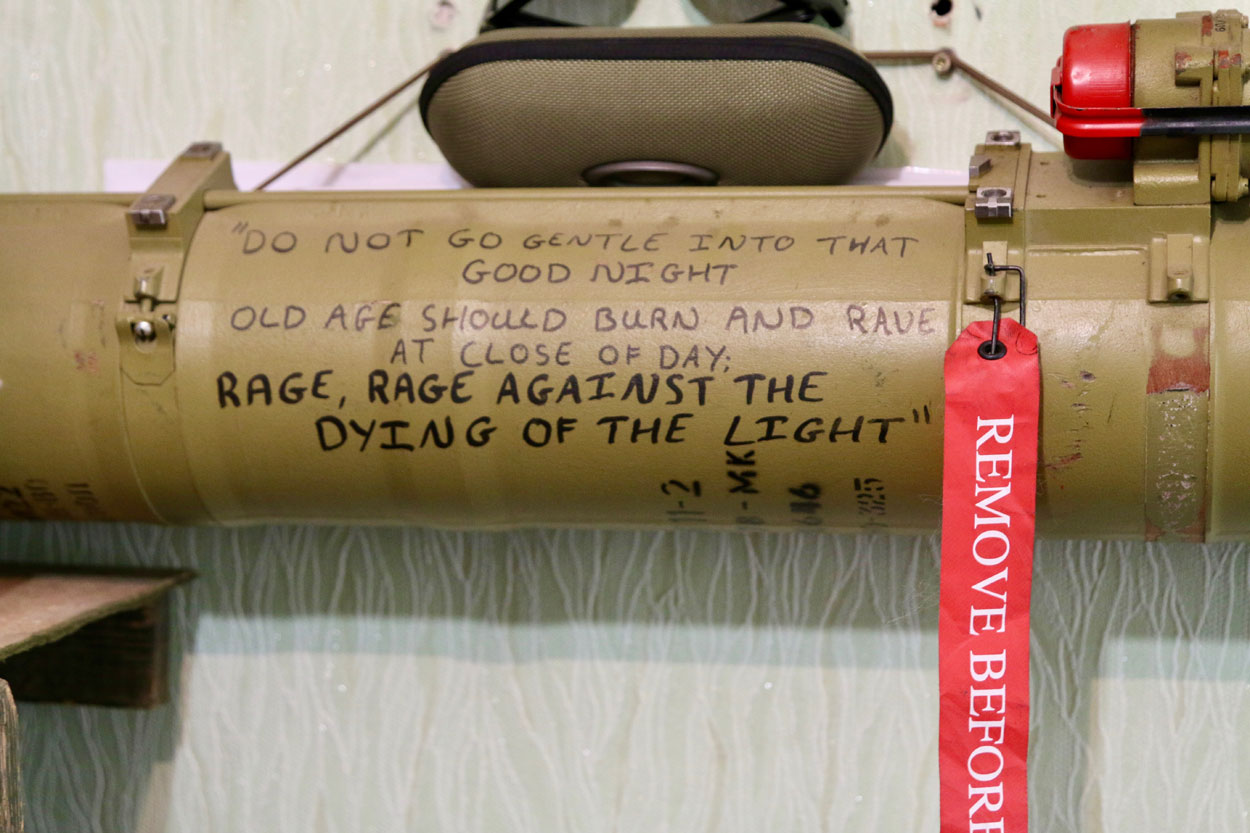

Gandolf, left, and Chris Garrett, right, show off some of the military equipment they had to pay for on their own.

More than three years and two failed cease-fires later, the war in Ukraine is now locked in a static, long-distance fight. Both sides abide, for the most part, by the February 2015 cease-fire’s edict to geographically freeze the war and not take new ground.

That said, the war continues as an indirect fire shooting gallery. About one-third of the war’s roughly 10,100 fatalities have occurred since the February 2015 cease-fire, known as Minsk II, went into effect. Soldiers on both sides remain, after more than two years under the cease-fire regime, hunkered down in trenches and ad hoc fortified positions within the ruined remains of cratered villages.

“This peace agreement is hard on the morale of the Ukrainian army,” the commander of the Azov Regiment’s 2nd Battalion, who goes by the nom de guerre “Kirt,” told The Daily Signal. “We’re committed to this war of liberation, but we’re tired. The peace agreement is a trap.”

According to NATO and Ukrainian officials, combined Russian-separatist forces comprise a joint force of about 3,000 Russian regulars and about 35,000 pro-Russian separatists and foreign mercenaries.

Yet, the Kremlin says it’s not involved in the war. According to Russia’s version of events, the separatist army is a grassroots insurgency composed of disgruntled factory workers and coal miners who pillaged Ukrainian army bases for their armaments.

Within the embattled Donbas region, comprising about 5 percent of Ukraine’s total land mass, this so-called separatist uprising has assembled 478 operational tanks, according to Ukrainian and U.S. officials—more than the combined number of tanks fielded by Germany, France, and the Czech Republic.

“It’s 100 percent a war against a Russian invasion, so how can we make a peace deal?” Kirt said. “Russia wants to maintain this war forever. We can stop this war only if we win this war.”

Ready for War

While the war simmers, the Azov Regiment is currently off the front lines, held in reserve in case of a combined Russian-separatist offensive. As at other places along the front lines, in Sector M where Azov is deployed (“M” stands for Mariupol), Ukrainian forces have stashed their heavy artillery and armor outside the buffer distance by which the Minsk II cease-fire mandates both sides pull their heavy weapons back from the front lines.

If Russia and its separatist proxies launched an offensive, Ukraine’s front line units would have to hold out using light weapons until the heavy stuff can be brought up to the front along with reinforcements from reserve units like the Azov Regiment.

The Azov Regiment’s troops have mixed emotions about being off the front lines. Some are itching to get into the fray to avenge the past few years of battlefield losses and retake Ukrainian territory now under the control of Russia’s proxies.

Other soldiers, however, acknowledge the importance of the time they now have available for training, as well as the psychological reprieve of not living under the 24/7 menace of enemy fire.

“Most guys want to get into some action, but I think that in this state of war it is almost pointless to be at the front, to live in the trenches and get mortared,” Kolomoets said. “Azov is more than capable of offensive actions, but mostly there’s none. My point is that I don’t like being left in the trenches, getting shelled or mortared and not allowed to do something about it.”

Since leaving the front lines in the summer of 2015, the Azov Regiment has stood up new training programs and has built its institutional framework, practically from the ground up. For the first time, for example, the unit has a specialized training course for its noncommissioned officers. An officer training program is also in the works.

“It’s hard to explain to our guys the need to prepare,” Kirt, the battalion commander, said. “Just a few kilometers away, Ukrainian soldiers are getting hurt. The main task as commanders of Azov is to explain to our guys the need to take it easy, to understand how important it is to train.”

Skill Sets

On this day at the Azov Regiment’s Urzuf base, a 33-year-old ex-British army soldier named Chris Garrett—who goes by the nom de guerre “Swampy”—leads 11 Azov Regiment soldiers through a training exercise to simulate the safe disposal of booby-trapped ordnance.

The soldiers all wear American-style multicam combat uniforms. Some wear blouses, others wear only T-shirts emblazoned with the Azov Regiment’s logo. Six of them wear covers—multicam baseball caps. Their footwear is split between tan combat boots and running shoes.

Garrett wears the U.S.-standard multicams with his sleeves rolled up. He is an explosive ordnance disposal, or EOD, specialist. A black-and-white EOD patch is on his right shoulder below a smaller patch denoting his blood type. He has a ZZ Top-length beard, tattooed arms, slicked back hair, and emotive, weathered eyes.

Garrett speaks in English to the Azov soldiers gathered around him for the day’s lesson; Kolomoets handles the translations.

Like most soldiers with true combat experience, Garrett is effusively polite, humble, and soft-spoken. Bravado among soldiers is usually reserved for those who have something to prove. Based on his friendly, low-key demeanor, Garrett is not looking to impress—he delivers his war stories like they’re self-deprecating jokes, not examples of true courage.

But, after three years of off-and-on wartime service with the Azov Regiment, Garrett’s stories from the front lines, along with the monumental task he has single-handedly shouldered, make quite an indelible impression, no matter how modestly he presents himself.

Garrett joined the unit in 2014 when it was still a volunteer partisan unit. Since that time, the Azov Regiment has become part of the Ukrainian National Guard, and Garrett, even though he has a British passport, is now an official Ukrainian National Guard soldier, drawing the standard 10,000 hryvnias a month (about $400) in pay like everyone else.

Garrett comes from the Isle of Man. He joined the British army at the age of 16 and served for one year before he was discharged due to an injury. He owned a tree surgery business on the Isle of Man for a few years before the siren call of war took its hold.

First it was to Karen State, a breakaway region in Burma and home to an ongoing civil war that began in 1949. He went there in 2012 as a volunteer, delivering humanitarian supplies and working to demine areas near where civilians live.

“There is something special about helping people live in safety,” Garrett said. “People like me are not trying to be heroes. We know that the heroes are the people who have to live alongside the explosive threats every day.”

Before Garrett ever set foot in Ukraine, it felt like his war.

“When the little green men turned up in Crimea, I knew that there were Russian forces invading the sovereign territory of Ukraine,” Garrett said. “This, in my mind, was a big problem and if someone annexed part of my country, I hope someone would come to help us in our time of need.”

He first arrived in Ukraine in September 2014 as a volunteer to deliver medical supplies and assist in demining operations. Not long after, he was a volunteer soldier fighting for Ukraine.

“I didn’t know what I was getting into,” Garrett said.

Baptism Under Fire

On February 14, 2015—Valentine’s Day—Garrett was caught in a particularly brutal battle in the front-line town of Shyrokyne, just outside of Mariupol.

Garrett was holed up with a hodge-podge of Ukrainian troops from different units in an observation post on the outskirts of Shyrokyne when combined Russian-separatist forces bombarded the position with Grad rockets. The rocket attack was a prelude to a full-on tank and infantry assault.

It was chaos. Firefights were breaking out all around. The Ukrainians were overwhelmed, cut off from the rest of their forces. They had no choice but to fall back. In the chaos and confusion of the retreat, and probably also partly due to the fact that he doesn’t speak Ukrainian or Russian, Garrett found himself separated. Totally alone as the enemy swarmed around him, closing in for the kill.

At one point, he ran alone across a street. As bullets nipped around him, Garrett came face to face with an enemy soldier. Garrett shot him in the chest with a sniper rifle. The enemy soldier dropped.

It was “just instinct,” Garrett said.

Soon, Garrett fortuitously reunited with two other Ukrainian soldiers—neither of whom spoke any English. Together, the trio bounded between destroyed homes, scurried across crumbled walls and through cratered gardens. They even crawled through a drainage pipe at one point as they dodged tank rounds and machine gun fire.

“A little bit of training can exponentially increase a soldier’s survivability,” says Chris Garrett, a British army veteran.

Garrett and his two Ukrainian comrades were trapped behind the enemy assault. So, with no better option other than surrender, they removed their patches and the reflective tape on their arms, which Ukrainian soldiers used at that time to identify themselves. Then, with their stomachs in their throats, the three of them stood up and walked through the embattled town in the open, pretending to be separatists.

When one of the Ukrainian soldiers spoke in Russian to a passing separatist soldier, Garrett just mutely observed. As the trio advanced toward the edge of town, closer to the Ukrainian lines, they came under fire from Ukrainian troops who mistook them as separatists.

They dove into a ditch for cover. Moments later, a well-placed tank round impacted inside the embankment. “The blast and shockwave rolled over us, deafening us and showering us with flame and dirt,” Garrett recalled, adding that he still has permanent hearing damage from the concussion.

The tank round set the surrounding grass on fire, perhaps concealing the trio as they scrambled to a nearby house where they sought shelter until nightfall. Then, under the cover of darkness, and with the disconcerting buzz of drones orbiting overhead, they furtively crept back toward the Ukrainian lines. Amid the chaos and confusion of the shifting battle lines, they were as likely to be shot at by their comrades as by the enemy.

Garrett and the two Ukrainians ultimately made it back to the Azov trenches. Their lives spared when one of the Ukrainian soldiers with Garrett yelled up to the trenches and explained that he had “Swampy” from Azov with him.

“The boys in the trenches looked tired and worn out from the day’s fighting,” Garrett said of what he saw when he made it back to the safety of his unit. “Sunken eyes and shaking uncontrollably. Everyone had had a tough day.”

Learning Curve

Garrett admitted his EOD experience was “mainly theoretical” before he arrived in Ukraine. “When I first got here, I was searching for trip wires in the middle of the night with my bare hands,” he said. “It was a very steep learning curve for me.”

But the fact that Garrett had any experience at all put him in high demand among the various Ukrainian outfits defending Mariupol.

Soon, Garrett was clearing minefields during combat operations and sneaking across no man’s land at night to scout for booby traps. In true World War I style, he even used explosives to carve out front-line trenches when doing it by hand would have been too dangerous due to the snipers and the shells.

“I was given free reign because I had any experience,” Garrett said. “I found a niche here, and I see the impact I’m making.”

“Swampy’s work has saved a lot of lives,” Kirt, the 2nd Battalion commander, said, using Garrett’s nom de guerre.

The explosive ordnance threat in Ukraine is mainly one of booby traps, land mines, and unexploded ordnance. Combined Russian-separatist forces have rarely used improvised explosive devices, or IEDs, on par with what Islamist militants have used to devastating effect on battlefields in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“They’re not at ISIS levels yet,” Garrett said, referring to the IED threat.

He added: “At the beginning of the war, everyone who had access to a hand grenade was stringing them across trees, doorways, along foot paths … but no one had any training to deal with the threat.”

Self Reliance

Garrett runs a makeshift training program for Azov, instructing small batches of Azov troops at a time in how to safely navigate minefields, dismantle booby traps, and handle unexploded ordnance. He said EOD training is uniquely cost and time effective, and should be a priority for the evolving unit.

“It’s the same as teaching someone CPR,” Garrett said. “A little bit of training can exponentially increase a soldier’s survivability.”

He added, “Once I train them, though, the trick is to get them the equipment they need.”

Despite the Azov Regiment’s official National Guard status, the unit still pays for most of its own supplies, runs its own training programs, and maintains its own facilities.

Overall, Azov troops say the National Guard mostly gives them what they need as far as weapons go. But most other supplies are of such low quality they have to buy replacements on their own. Those items include body armor vests, helmets, uniforms, rifle scopes, and footwear.

Soldiers’ pay is provided by the National Guard. So is ammunition, for the most part, which comes from Soviet-era stockpiles. The National Guard also gave the Azov Regiment a consignment of modified T-64 tanks.

However, Azov troops say there’s too much red tape and that it takes too long to request replacement equipment through official National Guard channels. It’s easier, they say, just to buy new stuff.

“These guys really want to change something, they want to save their country,” Kirt said. “But the government sometimes spoils the volunteer spirit.”

Garrett said he’s received, in sum, about “$200 worth” of training aids from the National Guard supply chain. Everything else he’s already bought or plans to buy in the future, he has to pay for out of his own pocket or through online donations.

He’s currently trying to raise enough money to buy a bomb disposal suit through the “GoFundMe” crowdfunding website (https://www.gofundme.com/eod-bomb-disposal-suit).

Garrett also wants to buy British individual mine clearing packs for every Azov soldier. At $15 a pop, he has to foot the bill himself for a key combat kit that can have an immediate, life-saving impact for soldiers on the front lines.

Although the Azov Regiment is off the front lines, Garrett said he “takes requests” from front-line units to clear mines, dismantle booby traps, and clear unexploded ordnance. He also works to remove dangerous explosives from civilian areas.

“People are always coming up with more interesting ways of killing each other, it’s tough to stay on top of that,” Garrett said.

One of Garrett’s projects is to map minefields and booby-trapped areas so that civilians can ultimately return home safely. He predicts it will take 20 years to properly demine the war zone in eastern Ukraine.

Warrior Tribe

There is a familial attitude among the Azov Regiment’s soldiers, which dispenses with much of the rigid traditions of military customs and courtesies.

The Azov Regiment has no institutional bedrock. It was forged specifically for the war it’s now fighting. Consequently, there isn’t much thought given to one’s position within the unit in any other context than fighting the war. There’s hardly any desire among most of Azov’s troops to advance in rank or to develop a career as a professional soldier. Military service is not seen as a career choice, but a wartime duty to defend the country from the existential threat of a Russian invasion.

In 2014, the Azov Battalion, as it was called then, had a war to fight and win. That was it. The unit was, in the truest sense, a warrior tribe.

Today, the Azov Regiment is still unique in its singular mission focus and warrior ethos. But the unit is also maturing, wisely dedicating its time off the front lines to training and building its institutional framework.

“Now that we’re off the front lines officially, we have the time to train,” Garrett said. “And when we go back to the front lines, we’ll spend less time messing about.”

Commanders like Kirt have taken the long view. They think the war in Ukraine could still escalate into a much larger, more lethal conflict. War-weary regular army and marine units, which have been weathering Russian shells rockets and mortars for years in the trenches, will rely on professional, well-trained, and fresh reserve units like the Azov should Russia ever launch a major offensive.

“In a high-intensity war, we can stop the Russian army,” Kirt said. “We stopped them before. We stopped them in 2014, and we can stop them again.”

He added: “At first, we fought for our liberation … we started as volunteers, now we want to be professional soldiers. Only a professional army has a chance to liberate our country.”

One challenge among Azov commanders is the broad set of possible threats they face. The unit is officially charged with monitoring the Sea of Azov coast to repel a maritime invasion. But a Russian offensive could also include an airborne assault, airstrikes, advancing tank columns, or rolling waves of artillery and rockets. Also, they have to always be ready to step into the trenches and join the conflict as it currently exists.

“We need to be like the [U.S. Army] Rangers,” Kirt said. “We don’t know when and where the enemy will exploit our weaknesses.”

The Education of a Warrior

The development of the Azov Regiment’s new soldiers contrasts with the experiences of many deployed Ukrainian soldiers—as well as that of the early days when the Azov Regiment was a volunteer partisan unit. The rush to man front-line units through mass conscription has meant an abbreviated training pipeline for many Ukrainian soldiers.

Azov’s newest recruits, however, now go through months of training, including specialized courses, before they ever see combat. That kind of measured maturation process in training, during which new recruits are indoctrinated with military discipline, is similar to what U.S. military personnel go through prior to combat.

Consequently, Azov’s commanders say the regiment is turning out better-trained, more professional soldiers than other Ukrainian military units.

“If you want to create a warrior, just put them in battle and 50 percent will survive,” said a 23-year-old platoon leader in the Azov Regiment’s 2nd Battalion, who goes by the nom de guerre “Gandolf.”

“But if you want to create a professional, you have to train him first,” Gandolf continued. “Then you put him into battle, after he’s trained. In that case, you create a professional warrior.”

A native of Ukraine’s capital city of Kyiv, Gandolf leads 20 soldiers. He does not, however, have a special rank to match his leadership position. The 23-year-old platoon leader is still what Ukrainians call a “simple soldier,” even though he has the equivalent responsibility of a noncommissioned officer, or even a lieutenant, in the U.S. military.

Chris Garrett, 33, joined the Azov Regiment in 2014 when it was still a volunteer partisan unit. “I didn’t know what I was getting into,” he says.

In May and June, Gandolf led a detachment of his troops—the newest recruits—on a brief deployment to the front-line town of Marinka on the invitation of the Ukrainian regular army’s 92nd Mechanized Brigade.

That short stint on the front lines in Marinka was an invaluable chance to experience combat firsthand, Gandolf said, and a proper capstone to the recruits’ military training.

“This static war is not one of assaulting positions or heavy fire, but it’s better than nothing,” Gandolf said. “The small unit experience is important for the rookies who have never been in battle.”

One key focus for the Azov Regiment’s commanders as they evolve the culture of their unit is to ditch the Soviet military mindset.

“The Soviets used a conscript army, like the Russians still do today,” Kirt said. “We’re training professional soldiers, who can think for themselves. We’re getting rid of the old system. We need a new type of defender, a new type of army.”

Kirt estimated that only 5 percent of Azov’s soldiers had attended one of Ukraine’s military academies, underscoring a break from the traditional, Soviet school of thought that still dominates throughout much of Ukraine’s armed forces.

“We prepare leaders, not commanders,” Kirt said. “We’re using the Western system, but also our own experience.”

He added: “It’s more important to learn how to improve our organization and our training than any specific skills or weapons.”

‘All Eyes Are on Us’

The Azov Regiment played a key role in some of the war’s most pivotal battles, including the 2014 liberation and defense of Mariupol, the deadly 2014 battle for Ilovaisk, as well as the grinding defense of Shyrokyne through 2015. Yet, despite its combat history, the Azov Regiment has a checkered reputation.

The group has been accused of war crimes and has drawn condemnation, including from U.S. lawmakers, for the neo-Nazi beliefs espoused by some soldiers within its ranks.

Azov soldiers, for their part, don’t shy away from acknowledging the far-right leanings of some of their comrades. “All eyes are on us,” Garrett said, referring to Azov’s complicated reputation. “But every military has some bad apples.”

Azov’s troops say the unit is inclusive of many different nationalities, faiths, and ethnicities. There is not an overall ideological bent to the unit, they say, other than a shared commitment to defending Ukraine.

“There’s only one ideology of Azov—it’s the liberation of the Ukrainian nation,” Kirt said. “We have people of all different backgrounds, from right and left, different religions. They’re all willing to die for Ukraine’s liberation.”