Son, Brother of American Hostages in Iran Pleads for Trump’s Help

Josh Siegel /

From a distance, Baquer Namazi taught—and showed—his sons how to see the best in people, and to help the needy.

A former Iranian governor, Baquer fled Iran after the 1979 revolution and emigrated to the U.S. in 1983.

In the U.S., Baquer started a long career with UNICEF, serving posts in Egypt, Somalia, and Kenya. Upon retirement, Baquer, 80, returned to Iran with his wife to spend his remaining years volunteering with projects to eradicate poverty.

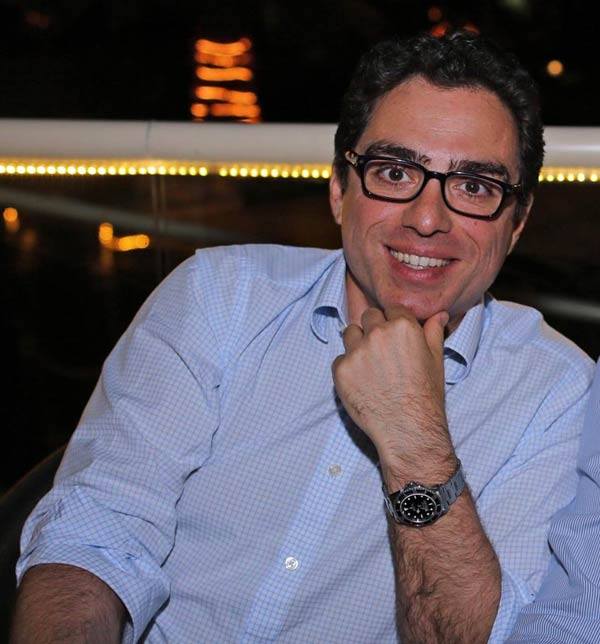

“He is an extremely optimistic person, which kills me,” says Baquer’s oldest son, Babak, 48. “I am more of a pessimist. He is not the type of person who would be comfortable in a comfortable environment.”

Today, Baquer is being held hostage by the Iranian government, his ambitions killed and spirit weakened.

“I always joked with my dad, and I would often say, ‘Dad, all these good deeds you’re doing—no good deed goes unpunished,’” Babak recalls in a recent interview with The Daily Signal from his small hotel room in the District of Columbia, where he traveled from his home in Dubai to advocate for U.S. government action to free his father.

“My mom recently visited my dad in prison, and for the first time, he said, ‘No deed goes unpunished, as Babak says.’ That broke my heart because that’s not him. My father, who is a giant of a human being and a giant of strength, was telling my mom, ‘I am getting weak.’”

‘Time Running Out’

On Oct. 18. 2016, Tehran sentenced Baquer and his youngest son, Siamak, 45—also a U.S. citizen—to 10 years in prison for collaborating with a foreign government—the United States.

The U.S. government, and Namazi family, dismiss the charges as baseless, and consider their detention as a play by Iran’s notorious Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps to taunt America, and extract concessions.

As the Obama administration tried and failed to negotiate with Iran to free Siamak and Baquer, Babak, an attorney, had stayed silent, not wanting to disrupt the fragile talks.

Baquer Namazi, 80, and his youngest son, Siamak, 45, are U.S. citizens who are being held hostage in Iran. (Photo: Courtesy of the Namazi family)

Since President Barack Obama left office in January, there has been no discussions between Iran and the U.S. government—on the Namazi case and that of other Americans detained or missing in Iran—according to the Iranian Foreign Ministry.

According to The Washington Post, at least four U.S. citizens with dual nationality—including the Namazis—and two green card holders, are imprisoned in Iran, and a former FBI agent who disappeared there a decade ago may still be alive.

So now, Babak is talking publicly, hoping to inspire the Trump administration to act at a time when relations between the U.S. and Iran are tense, and the new American government’s policy toward Tehran is unclear.

Babak said he was buoyed by President Donald Trump’s reaction to the Namazis’ sentencing, when, two weeks before the presidential election, the then-Republican nominee tweeted:

Well, Iran has done it again. Taken two of our people and asking for a fortune for their release. This doesn't happen if I'm president!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 23, 2016

A spokeswoman for the Trump administration’s National Security Council would not confirm whether negotiations are ongoing with Iran to free American hostages. The spokeswoman confirmed Babak met with a National Security Council official, and emphasized Trump is committed to securing the Namazis’ release.

“We are unwaveringly committed to the return of all U.S. citizens held in captivity in Iran,” the spokeswoman told The Daily Signal, insisting on anonymity to discuss a sensitive subject. “It’s a tremendous priority for the Trump administration in getting them returned home.”

Babak said he gave the Trump administration a simple message. His father, Baquer, who has had triple bypass heart surgery and has lost 25 pounds in prison, has been hospitalized twice since his detention.

“I came to Washington to highlight my family’s situation,” Babak says. “These are two American citizens being held captive in Iran. My father’s situation is extremely dire. I understand we are in a new U.S. administration. From a logical and rational point of view, I understand things take time. But from an emotional point of view, my father’s time is running out very quickly.”

‘A Horrible Year’

Since the Iran nuclear deal went into effect in January 2016, agents connected with the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps have escalated arrests of people with dual Iranian and foreign nationalities.

Under the nuclear deal, negotiated by the Obama administration and other Western powers, Tehran agreed to constrain its nuclear capability in exchange for billions of dollars in sanctions relief.

After the agreement was implemented, Iran released four detained Iranian-Americans and one American—also in January 2016—while the United States released seven detained Iranians.

The Obama administration later acknowledged it had provided $400 million in cash to Iran shortly after the Americans were freed, a payment critics described as ransom.

Babak and his attorney, Jared Genser of Freedom Now, say they expected Siamak, the younger Namazi brother, to be released as part of that agreement.

Genser and Babak say that after Siamak was not included in the deal, Iran had promised the Obama administration that it would release him, but instead, they arrested Baquer, the father.

“We were shocked and appalled when the deal was announced and we learned from television news that Siamak was not a part of it,” Genser told The Daily Signal in an interview. “Instead of releasing Siamak, the Iranian government double-downed and arrested his father.”

Siamak Namazi is a U.S.-educated consultant and scholar who has written about the humanitarian impact of U.S. and Western sanctions on Iran. (Photo: Courtesy of the Namazi family)

The Namazis’ problems began on July 18, 2015, when Siamak was trying to return home to Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates, after visiting his parents in Iran.

On that day, Babak says, Siamak was stopped at the Tehran airport by officials with the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps, and stripped of his passport. Siamak texted Babak that he would not be making it back to Dubai.

“When someone says I am being pulled aside at an airport, unfortunately in Iran what it means is that something not good has happened,” Babak says.

Siamak was released that day, but the Guards Corps summoned him to regular interrogation sessions over the next three months, Babak says.

Siamak, born in Iran and educated in the U.S., is a graduate of Tufts and Rutgers universities who once ran a consulting company that advised multinational corporations like Royal Dutch Shell about how to navigate Tehran’s complex business landscape.

He maintained an active public profile and was well known in the District, researching and writing about the humanitarian impact of U.S. and Western sanctions on Iran.

On Oct. 13, 2015, Siamak was arrested and taken to a prison in Tehran.

Baquer, residing in Iran with his wife, spent the ensuing months agitating for Siamak’s release, protesting in front of the prison, Babak said.

In February 2016, Baquer traveled to Dubai to rest and see Babak and his wife and two children.

Upon flying back to Iran on Feb. 22, Baquer was arrested at the Tehran airport by the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps and brought to the same prison as Siamak, his son.

The father and son do not share prison cells, and have never been allowed to see each other, Babak says. Both have been subjected to solitary confinement. Babak’s mother, whose name the family did not want to be published because she remains in Iran, is allowed weekly phone calls and monthly visits to the prison.

“It’s been a horrible year,” Babak says. “Who puts a 80-year-old man in solitary confinement? I cannot digest it as a human being.”

In October 2016, a year after Siamak was arrested, Iran’s judicial news service, Mizan, posted a video online that appeared to show him in the moments after his arrest, with his hands raised. The video is set to anti-American themed images, and foreboding music.

“I was extremely emotional—it was the first time I had seen my brother since he was taken,” Babak says.

The next day, in a brief, secret trial, Siamak and Baquer were sentenced to 10 years in prison.

Leaving a Void

When Babak thinks about the void without his father and brother, he reflects on his childhood.

Baquer, due to his global work with UNICEF, was not frequently present in Babak’s early life.

“He missed my birth,” Babak says. “He missed graduations. Because he was out there saving the world.”

https://twitter.com/letbaquergo/status/837951343700623360

Babak is not bitter about that distance. Baquer has more than made up for it by being an involved grandfather to Babak’s two children—a 15-year-old daughter and 17-year-old son who the Namazi family did not want The Daily Signal to name.

“He would take them to the movies, take them to get junk food, whatever they wanted,” Babak says.

Babak’s son is graduating high school this year. Baquer may not be present, this time, for entirely different reasons. Babak sometimes slips and refers to Babak in the past tense, as if his father isn’t here and won’t come back.

“I hate this, but I am spending a lot of time imagining the unimaginable,” says Babak, before stopping himself to restrain tears. “I am just wondering if I will see him again. I know he is dying for his grandchildren. We miss him. We miss him.”

‘Duty to Fight’

Babak’s on-again, off-again feelings of hopelessness are amplified because there is little he can control.

Babak, with his attorney Genser—who says he has worked about 40 hostage cases in his career—are hoping the Trump administration quickly pursues dialogue with the Iranians.

They worry about ongoing tensions between the two countries. Last month, the Trump administration imposed new sanctions on Tehran two days after the administration had put Iran “on notice” following a ballistic missile test.

The president has frequently criticized the nuclear deal with Iran, although the administration has not demonstrated it plans to scrap it. Trump’s revised travel ban signed this week temporarily bars visitors from six countries—including Iran.

“We are obviously very worried about the escalating tension between the U.S. and Iran,” Genser says. “Ultimately, the new administration has to decide what its approach is going to be. And if that will be direct engagement and discussions—which we hope and expect it will be—what precise set of measures will be put on the table to get it done?”

Babak says he has not spoken with the families of other American hostages in Iran. He said he has no plans to pursue negotiations outside the U.S. government.

In 2015, the Obama administration changed U.S. hostage policy not to seek prosecution of Americans who negotiate ransoms for family held abroad.

“The idea any American citizen could somehow do an end-around and engage the government of Iran directly and pressure them to give something is incredibly naive and unrealistic,” Genser says. “Only the U.S. government will be able to secure the release of hostages in Iran.”

Babak vows to do what he can, and looks back on his decision to go public with his family’s plight with no regrets.

“There is no right or wrong answer,” Babak says. “I believe this is the right thing to do right now. As a son, I have a duty to fight for my father and my brother’s life. The sense of urgency cannot be underscored enough. I do not want my father to die in prison.”