How Trump’s Campaign Comments Could Impact the Bergdahl Case

Cully Stimson / Hugh Danilack /

Should comments made by President Donald Trump during the campaign about Army Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl result in a military court dismissing the charges against the Army soldier?

Eugene Fidell, the top flight defense counsel for Bergdahl, has filed a motion to dismiss the charges and specifications against his client because then-candidate Trump called Bergdahl a “traitor” and suggested that he should be executed if convicted.

The military judge will hold a hearing on the motion, as is proper.

Without addressing the merits of this particular motion, it is quite clear that comments by a sitting president of the United States, or other senior officials, can have legal consequences to a pending federal case, whether that case is in federal district court, a military court-martial, or even a military commission.

But the novel question here is whether comments made by a private citizen should have any legal consequences in a pending federal case if that private citizen later becomes president of the United States.

Unlawful Command Influence

Recall that Bergdahl is alleged to have walked away from his post in Afghanistan in 2009 before being captured by the Taliban.

He was held until he was exchanged in a 2014 prisoner swap for five Taliban fighters imprisoned at Guantanamo Bay. Bergdahl was then charged with desertion and misbehavior before the enemy under Articles 85 and 99 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

The motion, filed on Jan. 20, exhaustively documents Trump’s comments about Bergdahl on the campaign trail from June 11, 2014, to Aug. 9, 2016.

It includes quotations from interviews and speeches at campaign rallies, as well as a video exhibit of candidate Trump’s public statements, and screenshots from Twitter and other televised speeches. These statements include candidate Trump repeatedly calling Bergdahl a “traitor” and suggesting that he should be executed.

Fidell (who is an acquaintance) argues that “President Trump’s statements deny Sgt. Bergdahl the due process right to a fair trial and constitute apparent unlawful command influence.”

Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl leaves the Fort Bragg courtroom facility after a motions hearing on Tuesday, May 17, 2016. (Photo: Andrew Craft/ZUMA Press/Newscom)

The charge of unlawful command influence is unique to the military justice system.

Because the military is comprised of men and women, each of whom has a rank and is subject to the lawful orders of superior officers, there is the very real concern that people may use superior rank improperly to influence individuals involved in a court-martial.

To alleviate that concern, Congress passed Article 37 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice, which states that “No person subject to [the Uniform Code of Military Justice] may attempt to coerce or, by any unauthorized means, influence the action of a court-martial … or any member thereof … in reaching the findings or sentence in any case … ”

To bring an allegation of unlawful command influence, the accused must show facts—which if true, constitute unlawful command influence—that the proceedings were unfair, and that the unlawful command influence was the cause of the unfairness.

Additionally, under United States v. Lewis, “Even if there was no actual unlawful command influence, there may be a question whether the influence of command placed an ‘intolerable strain on public perception of the military justice system.’”

According to United States v. Lewis, apparent unlawful command influence arises “where an objective, disinterested observer, fully informed of all the facts and circumstances, would harbor a significant doubt about the fairness of the proceeding.”

Fidell argues that, in the case of Trump’s comments about Bergdahl, “whether the circumstances are viewed through the prism of due process or as a matter of apparent [unlawful command influence], the charges and specifications should be dismissed.”

A Recent Case

It is clear that, under Article 37 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice, comments by a sitting president, attorney general, or other command authority regarding a pending federal case can have serious legal ramifications, and rightly so.

For example, in 2012, lawyers for Khalid Shaikh Mohammed—the mastermind of the 9/11 attacks—filed a motion to dismiss the charges against him due to unlawful command influence. In the motion, the defense referenced a long list of statements and interviews they argued constituted unlawful command influence.

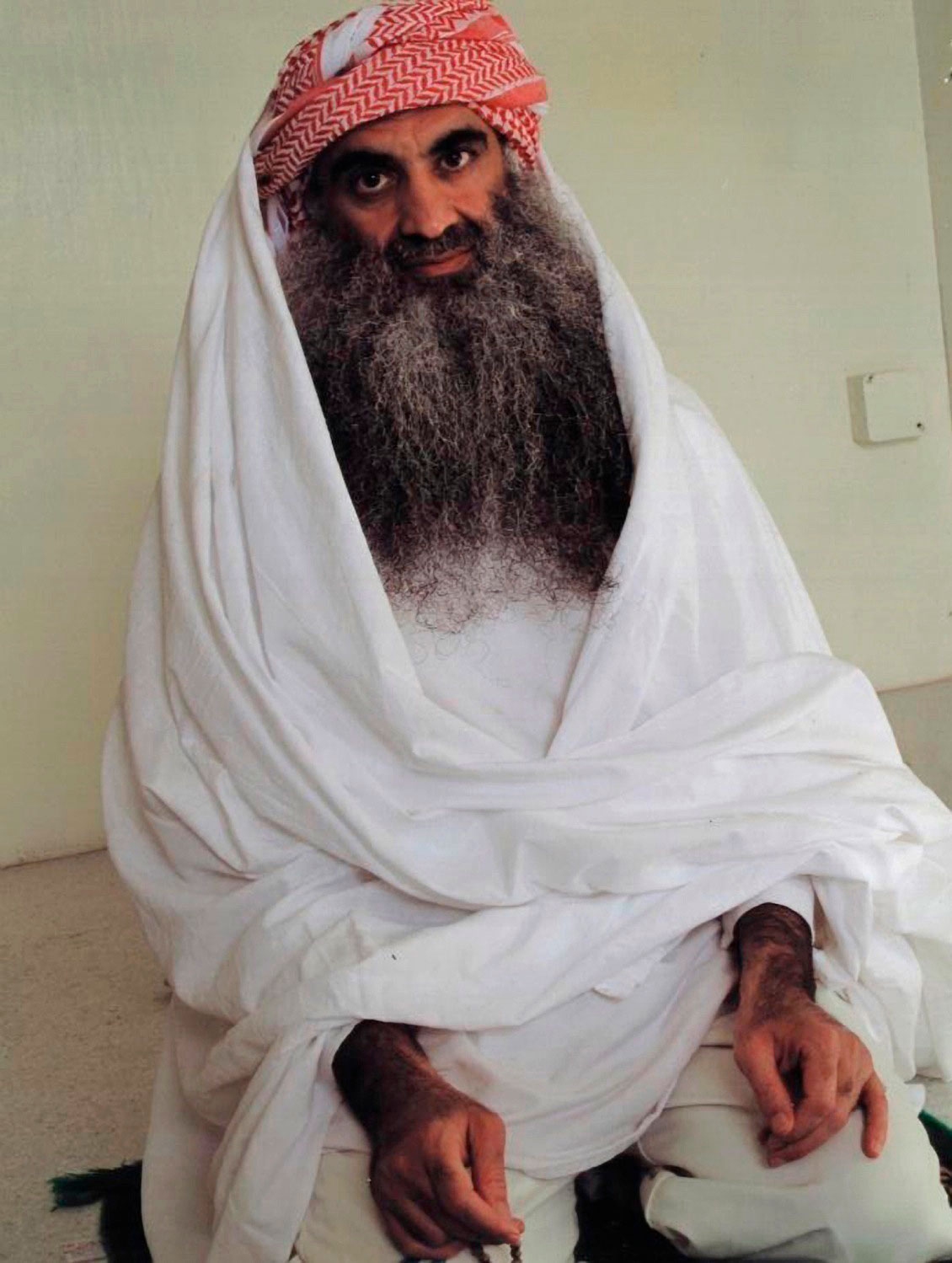

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the accused mastermind of the 9/11 attacks, is currently held at the Guantanamo Bay detention facility. (Photo: Red Cross/ZUMA Press/Newscom)

Notably, it included MSNBC anchor Chuck Todd’s interview with then-President Barack Obama on Nov. 18, 2009.

When asked by Todd whether he could understand why it would be offensive to people to have Mohammed receive all the legal privileges of an American citizen, Obama responded, “I don’t think it will be offensive at all when he’s convicted and when the death penalty is applied to him.”

When pressed about whether he was prejudging the case, Obama clarified that he was only saying that “people will not be offended if that’s the outcome.”

Further, in a news conference on Nov. 13, 2009, then-Attorney General Eric Holder stated in reference to trying Mohammed and others in federal court, “I would not have authorized the prosecution of these cases unless I was confident that our outcome would be a successful one.”

These statements, among many others, led the defense for Mohammed to file the motion to dismiss on May 11, 2012. A decision was not made until Apr. 5, 2016, in which Judge Col. James Pohl denied the motion to dismiss.

The case, however, is still ongoing. If Mohammed is convicted on appeal, his appellate attorneys may appeal the denial of the dismissal as one ground for appellate relief.

This nearly four-year delay in the trial of Mohammed should be instructive to the president, attorney general, and other command authorities that commenting on pending federal cases can have legal consequences.

It is important to note, however, that the charges in the Mohammed case were brought against a sitting president, attorney general, and other military commanders.

How Trump’s Case May Differ

In the case of Bergdahl, at the time Trump made his comments, he was merely a candidate for office—and thus, arguably, he was not subject to Article 37 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

The United States has yet to respond to the defense motion to dismiss.

Fidell acknowledges that this is the case and, consequently, he cited the doctrine of apparent unlawful command influence to argue in favor of dismissal.

Fidell argues that under the apparent unlawful command influence doctrine, dismissal is required to safeguard the credibility of the military justice system, which he asserts has been placed under a “powerful external influence” by comments that Trump made as a candidate.

However, it is still not clear that the apparent unlawful command influence doctrine developed under United States v. Lewis can be used to apply to comments made by candidate Trump. Indeed, Fidell offers limited support for the idea that a candidate’s statements can have legal consequences.

Rather, Fidell argues for dismissal on the grounds that there are no alternative remedies through extensive questioning of prospective jurors (called “voir dire”), curative instructions from the military judge, or other legal measures that will ensure a fair trial and safeguard the credibility of the military justice system.

Once again, it is not clear that this is the case.

In Pohl’s decision denying Mohammed’s motion to dismiss on charges of unlawful command influence, he cites the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals’ decision in the “Boston Bomber” trial in addressing cases that achieve significant media attention.

The court wrote in the case, In re Tsarnaev, “Thus, any high-profile case will receive significant media attention … Knowledge, however, does not equate to disqualifying prejudice.”

Pohl argues that the defense still has the option to show actual prejudice at trial and use other established legal means to ensure a fair trial.

The United States will, no doubt, oppose the motion to dismiss. And it would be unwise and unfair to predict how the military judge will rule on the motion.

That said, the allegations of actual and/or apparent unlawful command influence and their legal consequences should serve as a warning to Trump and other senior officials not to comment on the Bergdahl case, or any other pending federal cases—as Obama and Holder did before him.

Forewarned is forearmed.