Why Are Many Former Workers Not Even Applying for Job Openings?

Patrick Tyrrell /

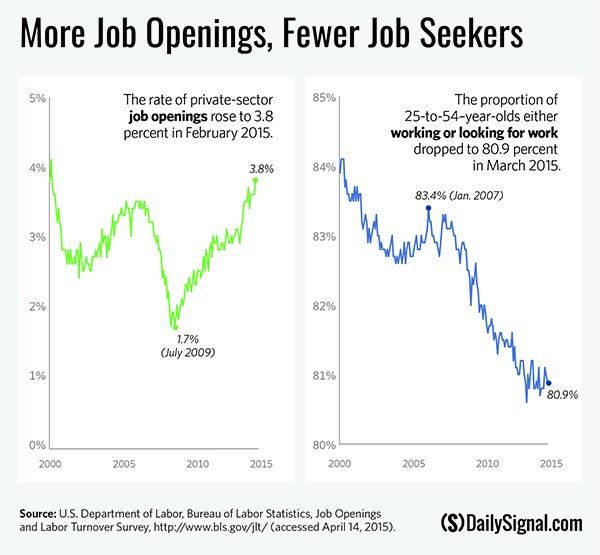

There was good news this month: private-sector job openings rose slightly in February, according to data released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Openings rose to 3.8 percent of all private-sector jobs and the job openings—the highest rate since January 2001. Other data for the month showed the unemployment rate for workers age 25-54 (often called prime age workers) ticked downward to 4.6 percent from 4.8 percent.

More people who want jobs are finding them, but there is something else going on as well. The labor force participation rate for prime age workers has continued to decline. Fewer of them are working or actively looking for work than before.

How can job openings stand at 14-year highs, but the labor force participation rate for prime age people hover around levels not seen since 1984?

University of Chicago economics professor Casey Mulligan suspects he knows why. As detailed in his 2012 book, and elaborated on more recently in his blog, and in The Wall Street Journal, Congress made major changes to anti-poverty subsidies and regulations during the Great Recession. All these changes provided more benefits that phase out as recipients earn more money.

For example, the federal Lifeline Assistance Program began to give free cell phones and free monthly cell phone usage to applicants if their income was low enough. Mortgage-assistance programs cut the mortgage payments of people if they were not working, but those with jobs still paid full price. The Obamacare health subsidies fall as earnings rise, which is a tax on labor activity.

Mulligan calculates that the marginal tax rate, that is the extra taxes paid, and government subsidies foregone on an extra dollar earned working if taking a job rose from 40 percent to 48 percent within two years of the onset of the Great Recession.

As the recession began, the labor force participation rate fell along with the job openings rate. But as job openings rebounded labor force participation remained stagnant.

People who had left the labor force did not come back. As Mulligan says, “Helping people is valuable but not free. The more you help low-income people, the more low-income people you’ll have. The more you help unemployed people, the more unemployed people you’ll have.”

Mulligan tells the story of a recruiter he met who had many people turn down jobs he offered them because “accepting a job would net them less than $2 per hour, so they would rather stay home.”

If people do not work for $2 per hour, that does not mean they are lazy. It means they are reasonable.

Unfortunately the decision to avoid work to avoid losing government benefits—while often rational in the short term—has terrible long-term effects. Skills atrophy the longer someone is out of work, and government benefits carry with them no chance for promotion or advancement.

To fix this, each existing government subsidy meant to help the poor and unemployed should be examined by lawmakers to determine whether it creates incentives to work or to stay on welfare. Work requirements should be strengthened on all means-tested assistance, and the tax system should be overhauled to ensure that it doesn’t penalize work. Moving people from welfare to the workforce is a win for individuals and a win for society as a whole. It’s time for the government to stop encouraging potential workers to stay home.